3 Artistic Defiance: Utilizing the Power of the Erotic and Sexuality

Artistic Defiance: Utilizing the Power of the Erotic and Sexuality

India Reinhardt

Introduction:

While facing incessant suppression by the patriarchal structure of the art world, female artists express their autonomy and transcend societal norms by utilizing the power of the erotic and sexuality in their artwork. Mediums like painting, sculpture, photography, and performance act as a lens through which female artists can reclaim agency, produce discussion about desire and empowerment, and inspire women globally. However, the male-dominated visual art world works very hard to subvert art made by women for women, blocking the true potential of erotic, feminist art to spark change. Audre Lorde’s text “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power” is perhaps the most relevant piece of writing that conveys this very idea of eroticism and patriarchal suppression. [1] Furthermore, in thinking about this suppression as an effect of male-controlled knowledge, Michel Foucault’s The History of Sexuality is a prominent text that explains this relationship between sexuality, power, and knowledge. [2]

When someone enters a museum or gallery space, they will realistically view little to no art created by women– but even if a brilliant piece by Frida Kahlo was positioned between a Warhol and a Matisse, the content of the work and society’s reception will be substantially different, purely because of her female identity and bold sexuality. At twenty-six important museums in America over the past decade, only 11 percent of all acquisitions and 14 percent of all exhibitions were of work by female artists. They generally continue to go under-recognized by museums, galleries, auctions, and society overall due to systemic and social sexism. When one thinks about, talks about, or searches online to find the most influential visual artists throughout history, most of them are male. This does not mean that women are less artistically talented, but instead proves that society has not given them the same platform. Art created by male artists has been celebrated historically for breaking barriers and making waves, but female artists who push the boundaries of contextual social conventions are time and time again punished with silence.

Additionally, there is the larger conversation of institutions today remaining male dominated, leaving no space for women to make decisions about the objectives of each museum or gallery and setting a patriarchal tone for the entire art world. In a study done in 2007, it was found that only 25% of the largest museums in the US were led by a female director. [3] This brings up questions about how we can deconstruct the overall structure– would this be done best from within the system or outside of it? Another text of Lorde’s, “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” provides an argument that details the urgency of separating ourselves from systems to deconstruct them. [4] This paper will discuss the ways in which her theory has inspired artists to challenge institutions’ patriarchal structures through provocative art and unashamed expression.

It is equally as important to expose the patriarchal system of the art world and celebrate the female artists who have pushed boundaries and made history. Without visualizations of the pleasure of being a woman– the joy, the beauty, the pain– in artworks accessible to all, many women would not have experienced revelations about their own relationship to their mind and body. Female artists have played a large part in furthering feminist movements, while constantly receiving societal backlash for creating erotic imagery, pieces dedicated to portraying sexual liberation and celebrating different female identities. They work to challenge “sex negativity,” a Western concept discussed in Gayle S. Rubin’s text, “Thinking Sex” to an extent that has changed the world. [5] This analysis will discuss the ways in which female artists work to express their sexuality and eroticism through art, and additionally, the ways in which patriarchal power structures consistently stand in the way.

Theoretical Framework: The Foundations of Eroticism, Sexuality, and Power

To understand how a major societal problem affects different, more specific socio-political environments with the purpose of challenging the current standard, it is important to become educated on the concepts involved through key texts. In this case, where the goal is to understand how systems of power have worked to silence female artists who utilize the power of the erotic and sexuality in their pieces, it is first necessary to comprehend the true meaning of eroticism, the history of sexuality, society’s relationship to these concepts and the power dynamics involved. This can be done by analyzing four main texts: “Uses of the Erotic” and “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” by Audre Lorde, The History of Sexuality by Michel Foucault and “Thinking Sex” by Gayle S. Rubin. These texts, themselves, do not grapple with the dilemmas of the art world, but instead shape our ability to recognize them by providing contextual analysis and historical context.

Firstly, In Audre Lorde’s 1978 essay, “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power,” she explores the notion of the erotic as a source of power that can transform all aspects of society through individuals’ personal acceptance. Lorde describes the erotic as an intimate connection to one’s desires, body, and mind: “The erotic is a resource within each of us that lies in a deeply female and spiritual plane, firmly rooted in the power of our unexpressed or unrecognized feeling” (87). The problem she outlines, however, is how this resource has been subdued and warped. She makes the argument that by silencing the erotic through shaming, fear, and embarrassment, we are experiencing a loss of personal power and connection to our bodies, furthering the patriarchy and promoting heteronormativity. The author encourages us to embrace the erotic and use it as a tool to unlock newfound creativity, expression, and resistance. By accepting the erotic, it would change societal norms as we know them and create a space to challenge dominant narratives. [6] Visual art is one of the most popular forms of expression and one of the most impactful as well. This very idea of the erotic as power is what many female artists attempt to emanate from within their artwork, in hopes of claiming their autonomy and inspiring women across the globe. Eroticism is the root of expressions of desire, sensuality, sexuality, and the complexities of female identities. By harnessing this power, female artists have provoked conversations about pleasure and the many ways that one can experience womanhood. Discussions of “womanhood” have historically been in reference and catered to cisgendered white women, but visual art acts as a way for women of color, trans women, queer women, and low-income female artists to connect, inspire others, and express themselves.

In another text by Lorde, “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” the author analyzes the limitations of attempting to destroy or change a system from within it, especially by using the tools that endorse the system itself. It emphasizes the need for new approaches to reimagining structures, instead of relying on current oppressive systems to create societal change. [7] In thinking about the art world, can female activists successfully dismantle art institutions from within them? For instance, museums are one of the biggest ways people gain historical information, make statements, and spread opinions, so it seems difficult to imagine an art collective remaining timelessly relevant and influential without having to use systemic tools to increase their reach. Female artists have long been at the forefront of challenging art institutions and reforming boundaries, including creating art that reclaims female sexuality, a topic controlled historically by male authorities.

In Michel Foucault’s The History of Sexuality, he analyzed how the 19th century sparked a significant shift in how Western society understood and discussed the topic of sexuality. He brings up the repressive hypothesis and argues that instead of sexuality being straightforwardly repressed, it was instead increasingly regulated by authority powers, bringing in the relationship between sexuality, knowledge, and power. Foucault delves into how discourse surrounding sexuality changed and evolved, beginning to focus on understanding sexual behavior and learning how to categorize it. This means of controlling knowledge about sexual behaviors contributed heavily to our societal formation of power structures. [8] This argument is extremely relevant when examining the restrictions on female artists regarding their expression of sexuality in their art. They often face the dilemma of how radically they should explore and express their sexuality; how much they can push these concepts without being regulated and censored by power structures such as museum directors, communication networks, and financial infrastructures. In thinking specifically about these choices of expression, each artist experiences a very different life, and in turn has a very different relationship to sexuality. Not all forms of sexuality are received in the same way; there are types that are more accepted within society, and ones that are less so.

“Thinking Sex,” by Gayle Rubin, takes Foucault’s analysis of power and sexuality further, continuing to challenge dominant narratives that govern sexual identities and behaviors. The author conceptualizes and later visualizes the “charmed circle” versus the “demonized other,” a double-layered pie chart of sorts that illuminates how certain forms of sexuality are privileged, while others are scrutinized. By identifying, in even more detail, the levels of hierarchies embedded in sexual systems and knowledge, Rubin calls readers to critique the mechanisms that control sexual expression and call for greater inclusivity. [9] Women who explore eroticism and sexuality in their art often encounter heightened judgment and scrutiny, as their art calls to question “acceptable” sexual expression. Additionally, and more specifically, artists who shed light on sexuality that is not necessarily vanilla, heterosexual, and monogamous are more subjected to negative reactions and silencing. In order to understand the gravity of the patriarchal suppression of the erotic and sexual art made by women for women, it is first necessary to know the statistics surrounding female artists’ representation within art spaces.

The Case: Overall Trends and Artist Kubra Khademi

Without acknowledging more generally the discriminations and limitations women face in the art world, it is impossible to have a rounded understanding of how the content female artists express in their artwork has an additional impact on the statistics. As the Director of the National Museum of Women in the Arts once said, “People in the art world want to think we are achieving parity more quickly than we are.” [10] Discrimination against female artists takes many forms; difference in schooling and in pay, shortage of gallery support, and less representation in museums. The most expensive piece of work by a living woman artist at an auction was Jenny Saville’s painting, Propped (1992), which sold for 12.4 million dollars during 2018. While this is incredible, when compared to a Jeff Koons work that sold for 91.1 million in 2019, it pales in comparison. After an investigation by Artnet News and In Other Words, it was found that out of a total of 260,470 works of art that have entered museums’ permanent placements in the US, only 29,247 were created by women. It was also revealed that Black women made up just 3.3 percent of the total number of female artists whose work had been picked up by United States foundations, with women from other minority groups representing even less.

Considering the fact that women make up more than half of the population in America, it’s not a coincidence that all of these numbers are so low. Additionally, gender-based statistics often do not acknowledge race and ethnicity, disregarding the dramatically low percent of Latina, Asian, and Indigenous female artists represented in the art world. Attention has been brought to the fact that galleries discriminate against women for the same reasons the broader market does. They are skeptical of female artists’ ability to have great success. Studies have shown that women are suggested to have fewer connections that would benefit the galleries, as well as the fact that dealers are concerned about them taking more time off to pursue other careers or have children. [11] This statement is extremely prejudiced and founded on the sexist, patriarchal mindset present in all institutions.

Not only should female artists be given equal exposure in museums, galleries, and other societal contexts, but they should be additionally respected for their transcending contributions to the art world while simultaneously being subjected to discrimination and stereotyping. Because women have experienced systemic oppression fueled by patriarchal sexism, a natural response by female artists would be wanting to create discussion through a creative outlet that challenges the boundaries attempting to limit them. It is in turn ironic that they then get silenced by the very system that they are responding to. For example, Kubra Khademi is a feminist Afghan artist who lives in exile, after she was forced from her home country in 2015 for performing a feminist, political piece called “Armor,” where she walked down the streets of Kabul in a steel breastplate that emphasized her feminine shape. It was in response to public harassment of women in conservative cultures.

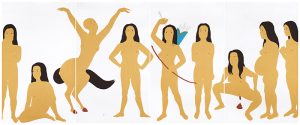

Later that year, she was placed on a list of the “most powerless people in the art world,” an article by Hyperallergic that attempted to comically acknowledge artists who had received very little support. [12] Not only is it controversial that this list exists, as powerless is a very impactful and damaging word, but it also seems undeniable that the list consists mostly of women and racial minorities. Often, “powerless” has been used to describe women in harmful positions where they have no autonomy or decision-making abilities, as a dominating male force has assumed the position with more power. Khademi sought asylum in France, where she is now a citizen, and had a solo show in 2021, responding to the ways in which her home country failed her. Many of her works include the erotic writings of the 13th-century poet Rumi as an homage to the “below-the-belt” language that many Afghan women use amongst each other as code; an oral tradition of resistance to the patriarchal order. An example of this is the artist’s solo exhibition title, From the Two Page Book, which is code for “from my ass.” Her work is sexual, erotic, cheeky and vulgar, featuring women “taking a shit” with smooth, naked bodies; laughing at the “sacredness” of women and girls, the female innocence that must be protected. [13] In an interview, the artist reflected on her childhood: “I have five sisters and four brothers. When my father died, my brother took over. If it wasn’t him, it would have been another man: an uncle, a neighbor. This isn’t a theoretical argument – it all comes from my life experience. I’ve grown up in a culture and society where being an artist and a woman is a terrible thing, because art is all about self-expression.” [14] She stated that the shame she felt as a child for expressing herself artistically disappeared as she grew older. She additionally emphasized that we have to celebrate living without any guilt, which is at the very foundation of Lorde’s analysis of the erotic. Khademi created erotic, sexual art that made a statement, received death threats and was thrown out of her home, and then continued to make art that only grew more powerful after what she had been through.

Analysis: How Do We Achieve Progress? Inside Vs. Outside of Oppressive Systems

In thinking about the statistics of female artists being under-represented in the art world and the discrimination they face in art-based environments, The History of Sexuality details how the relationship between power, sexuality, and knowledge affect societal structures. [15] As patriarchal systems have controlled and regulated knowledge, they have had authority over which artists are represented by galleries and museums. It additionally seems logical that because they hold control over which art is made available to the public in institutional settings, people won’t be as exposed to art made by women for women, thus lowering the arts’ value. This discourages female artists from accurately pricing their pieces, as art made by famous male artists has been deemed of higher value. Similarly, “Thinking Sex” discusses the types of expressions of sexuality that are socially acceptable versus inappropriate in the eyes of our patriarchal system. [16] Rubin’s argument that male-dominated society does not feel comfortable with evocative and sexual expressions supports the fact that female artists make up such a small percentage of exhibitions and auction sales. Although very few studies have focused on female erotic suppression in the art world, which says something in of itself, it is unfortunately realistic that because female artists often use art as a form of feminist empowerment, gallerists and curators have a harder time endorsing them. It does not benefit them as much as, say, promoting a historically loved piece by Andy Warhol, a male artist whose work focused on subjects unrelated to gender or sexuality.

In relation to Kubra Khademi’s empowering story of perseverance after exile, “Uses of the Erotic” captures the message of her art before and after beginning her new life in France. She felt empowered in her body as an individual who knew what she wanted and how to express it, creating pieces that laugh at current gender dynamics. Her art responds to Lorde’s messages about the freedom of the erotic and the beauty in exploration of sexuality. Her pieces are comical and often crude metaphors that address issues of women’s rights and the oppressive nature of the patriarchy. [17] In doing this, she is setting an example that there are ways to fight back against domineering systems that attempt to regulate female artists. Considering “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” Khademi, in a way, left the Master’s House (Kabul) behind as she was threatened and kicked out, starting a new life where she was free to harness her erotic power and create influential art in Parisian solo shows, without having to adhere to conservative culture. However, in terms of the art world, the Master’s House has and always will be institutions that hold the power over who is represented. Without taking credit away from the well deserving artists who have made names for themselves, it is undeniable that there is intention behind why museums and galleries feature each artist they choose to represent. It must always benefit them in some way, and although many female artists know that they have been the “chosen women” selected to show their art amongst a disproportionate number of men, that fact is understandably not enough for them to turn down an opportunity. There is still a lot of progress that must be made to either get to a place in which all female artists are able to receive support independently or spark change within institutions. In thinking about the headway we have made and the adaptations that still need to occur, many groups of artists fighting gender inequality in the arts, like the Guerilla Girls, work to protest against discrimination at an international level. Outside of large institutions, a step in the right direction would be for independent curators and forward-thinking organizations to create frameworks that represent female artists of all identities. Now more than ever, all artists and people in privileged positions of power within the art world need to continue to challenge the systems responsible for female artistic suppression and inequality.

Conclusion:

The goal of this paper has been to understand female artists’ expressions of eroticism and sexuality through their work and the ways in which patriarchal oppressive systems attempt to thwart their success, using the lens of literary texts and the artwork of Kubra Khademi. This successfully created a space to understand the problems within the art world as a component of larger systemic sexism. The History of Sexuality and “Thinking Sex” provided helpful context for the unbelievably statistics of female under-representation in art spaces. Similarly, both of Lorde’s texts, “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power” and “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” defined expertly the importance of expressing eroticism in a male-dominated society and the need to separate oneself from large, oppressive systems in order to successfully create change. This intertwined with artists’ expression of power and sexuality within their art and art institutions as maintaining patriarchal structures.

In thinking more conceptually about who runs these structures, wealthy men invested in the modern art world dominate decisions of which artists gain popularity or get thrown aside, and rarely choose to support female artists who create work relating to sexual liberation and eroticism, as these are the very movements the patriarchy works to suppress in order to maintain an unbalanced power dynamic. Art depicting the female experience, body, and pleasure through a lens with no trace of objectification for the male gaze makes men uncomfortable, a statement supported by Rubin’s text, especially because it eliminates the power they historically hold in relation to knowledge and sexuality. This is the very reason, even in the modern day, behind many small subordinations female artists are subjected to in the art world. Even just the term “female artist” indicates that “artist” alone implies men and is derived from the unspoken truth that society views female artists in relation to male artists. While patriarchal systems attempt to subdue female artists’ expressions of eroticism and sexuality, they simultaneously fuel the continuation of art that inspires women globally to feel empowered and to listen to their own desires. Experience shapes art. Despite enduring patriarchal oppression and systematic subjugation from institutional forces, female artists have consistently broken boundaries and created sexually liberating, erotic art; reclaiming agency, creating dialogue about female empowerment, and inspiring all who view it.

Bibliography:

Epps, Philomena. Kubra Khademi: The Unbearable Artist. Oct. 9, 2021.

Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality, Volume I: An Introduction. Pantheon Books, N.Y., 1976. pp. 3-49

Kheriji-Watts. Kubra Khademi’s Erotic and Coded Paintings of Women. Hyperallergic, 2021.

Lorde, Audre. The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House. Trumansburg, N.Y.: Crossing Press, 1984 pp. 110-113

Lorde, Audre. Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power. Trumansburg, N.Y.: Crossing Press, 1984. pp. 87-91

National Museum of Women in the Arts. “Get the Facts.” National Museum of Women

in the Arts. Accessed December 15, 2020. https://nmwa.org/support/advocacy/

get-facts/.

Rubin, Gayle. Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality. Routledge & Kegan, 1984. pp. 3-43

Schwarzer, Marjorie. “Women in the Temple: Gender and Leadership in Museums,” in Gender, Sexuality, and Museums, ed. Amy K. Levin, 16-27. New York: Routledge, 2010.

- Lorde, Audre. The Master's Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House. Trumansburg, N.Y.: Crossing Press, 1984 pp. 110-113 ↵

- Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality, Volume I: An Introduction. Pantheon Books, N.Y., 1976. pp. 3-49 ↵

- Schwarzer, Marjorie. “Women in the Temple: Gender and Leadership in Museums,” in Gender, Sexuality, and Museums, ed. Amy K. Levin, 16-27. New York: Routledge, 2010. ↵

- Lorde, Audre. The Master's Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House. Trumansburg, N.Y.: Crossing Press, 1984 pp. 110-113 ↵

- Rubin, Gayle. Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality. Routledge & Kegan, 1984. pp. 3-43 ↵

- Lorde, Audre. Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power. Trumansburg, N.Y.: Crossing Press, 1984. pp. 87-91 ↵

- Lorde, Audre. The Master's Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House. Trumansburg, N.Y.: Crossing Press, 1984 pp. 110-113 ↵

- Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality, Volume I: An Introduction. Pantheon Books, N.Y., 1976. pp. 3-49 ↵

- Rubin, Gayle. Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality. Routledge & Kegan, 1984. pp. 3-43 ↵

- National Museum of Women in the Arts. "Get the Facts." National Museum of Women in the Arts. Accessed December 15, 2020. https://nmwa.org/support/advocacy/get-facts/. ↵

- National Museum of Women in the Arts. "Get the Facts." ↵

- Kheriji-Watts. Kubra Khademi’s Erotic and Coded Paintings of Women. Hyperallergic, 2021. https://hyperallergic.com/628269/kubra-khademi-galerie-eric-mouchet/ ↵

- Kheriji-Watts. Kubra Khademi’s Erotic and Coded Paintings of Women. Hyperallergic, 2021. https://hyperallergic.com/628269/kubra-khademi-galerie-eric-mouchet/ ↵

- Epps, Philomena. Kubra Khademi: The Unbearable Artist. Oct. 9, 2021. https://various-artists.com/kubra-khademi/ ↵

- Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality, Volume I: An Introduction. Pantheon Books, N.Y., 1976. pp. 3-49 ↵

- Rubin, Gayle. Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality. Routledge & Kegan, 1984. pp. 3-43 ↵

- Kheriji-Watts. Kubra Khademi’s Erotic and Coded Paintings of Women. Hyperallergic, 2021. https://hyperallergic.com/628269/kubra-khademi-galerie-eric-mouchet/ ↵