12 Colonial Gender, Masculine Violence, and Indigenous Masculinities as Resistance

Introduction: The Monomyth of Masculinity

A rage ignited in me the first time I understood that patriarchy meant that I would always fear for my body. Raised as a White girl, I was told to be on guard. I wasn’t told what to be afraid of, just that I should always watch out, look over my shoulder, never walk alone. Coupled with this cultural messaging was an embodied fear stemming from experiences I’d had with men and boys that left me feeling violated, vulnerable, and unsafe. The connection between men, masculinity, and violence was a given. Masculinity was violence. It was the source of my frustration, my anger, my fear.

When confronting patriarchy, the simplest solution is to declare masculinity evil. Masculinity becomes an oppressive force synonymous with patriarchy itself. But, as eco-feminist scholar Sophie Strand reminds us, “there is always biodiversity behind a monomyth.” (Chayne and Strand 2003). Manhood, masculinity, and violence have become synonymous, but their relationship is not static, universal, or ubiquitous across time and space. Patriarchal masculinity in North America is intertwined with histories of settler colonialism, where modes of masculinity that prioritized extraction, domination, individualism, and violence against land and people have evolved and shifted to continue the American settler colonial project. This violent mode of masculinity was present not only in North America but amongst colonizers and colonial states across the Americas and the rest of the world.

In the field of gender studies, the term “hegemonic masculinity” has risen in popularity to describe and critique modern patriarchal gender. The term hegemonic masculinity was first proposed in the 1980s to describe the “pattern of practice that allowed men’s dominance over women to continue” (Connell and James 2005, 832). This theory of masculinity did not posit masculinity as fixed or natural. Instead, it theorized that hegemonic masculinity, as a form of masculinity elevated above other, “lesser” masculinities, was normative in that it embodied the ideal way to be a man, which ideologically relied on hierarchy and the patriarchal subordination of women (Connell and James 2005). This concept of hegemonic masculinity is similar to what I refer to as colonial masculinities to acknowledge the interwoven histories of colonialism and gender construction that have created hegemonic masculinities (Lugones 2016). While colonial masculinity as a term and construct is not limited to North America, this paper will discuss the evolutions and constructions of masculinity in the context of North American patriarchy and settler colonialism.

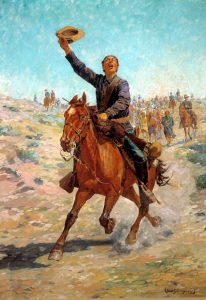

Using a framework of Indigenous feminisms, this paper will trace colonial masculinity in North America and its relationship to the continued violence against Indigenous peoples and lands. I will first focus on the creation of the mythic Anglo-American Cowboy as a moment in America’s history that reveals a crisis in the production of colonial masculinity, suggesting its fluidity and vulnerability. This case demonstrates that hegemonic masculinity as it exists today is not inherent or unchanging. It also provides insight into how colonial masculinities have evolved in their relationship to Indigenous peoples and land to reshape the ecosystems that they inhabit along the logics of extractivism, patriarchy, and white supremacy. I will also discuss the evolving gender identities of men in the Karuk Tribe of Northern California as an example of alternative masculinities. Karuk masculinity challenges the singular story of colonial masculinity in that its expression is not inherently violent and hierarchical but instead reciprocal.

Literature Review: Colonial and Indigenous Gender

Luhui Whitebear defines settler colonialism as “the systems, mindsets, and violence that are embedded in our everyday lives in ways that continue to center and prioritize Euro-centric ideals as superior to Indigenous-based ways of knowing and living” (Whitebear 2020). Whitebear argues that these systems are built through the genocide of Indigenous Americans, colonialism, and the conquest and exploitation of Indigenous land and peoples (Whitebear 2020). Whitebear describes Indigenous connection to land as centered in reciprocity in contrast to a settler-colonial approach, which centers itself on extraction and profit. In the context of settler-colonialism violence, Whitebear stresses that indigenous bodies and land are intertwined. (Whitebear 2020)

Along similar lines, Sabine Lang’s descriptions of Indigenous non-binary gender systems in Native American men-women, lesbians, two-spirits: Contemporary and historical perspective challenge the colonial logic of gender as inherent and unchanging. Lang explains that pre-colonization, it was common in Indigenous societies for gender roles to be formed by occupational preferences (Lang 2016). Many Indigenous tribes had (and to the extent that they were able to resist colonial ways of thinking, continue to have) gender systems that make room for shifts in gender roles and identities within an individual’s lifetime (Lang 2016). Many also have gender systems that are non-binary in that they often include third and fourth gender categories (Lang 2016). These diverse gender systems are the targets of colonization and forced assimilation, which has significantly impacted the traditions of gender diversity, making tribal groups who once had traditions of gender and sexual diversity conform with colonial notions of gender and sex and even obscure the existence of prior gender systems and understandings (Lang 2016).

In her essay, The Coloniality of Gender, Maria Lugones offers another crucial theoretical contribution to understanding the relationship between gender and colonization. Lugones weaves Anibal Quijano’s concept of the coloniality of power with Third World and Women of Color Feminisms’ gender analysis. Quijano’s conception of the coloniality of power describes a structure of power based on domination, exploitation, and conflict in controlling sex, labor, collective authority, and resources (Lugones 2016). European colonialism, Lugones explains, is based on the notion of coloniality of power and a conception of modernity, which posits a singular way of knowing: “rationality,” which is situated as the only “right” way to know (Lugones 2016). Lugones explains that while colonists saw gender as inherent, fixed, and biological, they also viewed Indigenous genders as straying from sexual dimorphism and, therefore, deviant and perverse. This is what she calls “the dark side” and the “light side” of the colonial/modern gender system, where while “the light side” is necessarily sexually dimorphic, the “dark side” is not (Lugones 2016). This deviance was considered a moral justification for assimilation and colonization (Lugones 2016).

Judith Butler’s gender performativity theory also challenges colonial masculinities’ common assertion that gender is essential. Rather than seeing gender as fixed, essential biology informed by an assumed binary sex, Butler’s performativity theory contextualizes gender as socially constructed and imposed upon the body (Butler 2015). Control over the production of gender, they argue, lies not with the individual but instead controlled by larger norms that produce gender as a regulating and constraining force on bodies (Butler 2015). Gender is linked to the creation of a human subject, where gendering is a cultural condition for becoming human (Butler 2015). For example, when an infant is born, they shift from being “it” (inhuman) to “he” or “she” and thus both gendered and human (Butler 2015, 7). When people are not “properly gendered,” Butler explains, their humanity is doubted (Butler 2015). This concept is paralleled in Lugones’ explanation of the dark/light side of gender, where Indigenous genders and sexualities were either gendered, human, and sexually dimorphic, or inhuman and perverse.

Relevant to understanding how gender, bodies, and colonialism are interrelated is the Latin American theory of cuerpo-territorio or “body-earth territory” (Arcangelis and Quiroga 2023). Cuerpo-territorio is a politic and frame of analysis that conceptualizes colonialism as inherently patriarchal and understands violence against the body, particularly women’s bodies, as interlinked with violence against land along the logics of colonial extraction (Arcangelis and Quiroga 2023). Cuerpo-territorio understands human life as inherently interconnected with that of the more-than-human (land, plants, waterways, non-human animals, spirits, etc.) (Arcangelis and Quiroga 2023). While cuerpo-territorio is not a theory explicitly used by many Indigenous feminists across Turtle Island, the concept mirrors many Indigenous feminists across the continent, including Whitebear, having similar conceptions of connection between body and land, reciprocity, and the patriarchal nature of colonialism (Arcangelis and Quiroga 2023).

Colonial Masculinity: The Cowboy

In the nineteenth century, colonial masculinity entered a period of crisis when anxieties about the decline of masculinity rose as the values of the Eastern colonies became increasingly defined by urbanity, manners, and a sense of “gentlemanliness” (Smith 2021). Eastern settler men worried that White, elite, patriarchal power was in decline as the political influence of working-class and immigrant men and the suffragette movement grew, as well as the vanishing of the American frontier as a space where colonial masculinity could be performed (Smith 2021). These anxieties were followed by a resurgence of masculinity connected to violence through the Indian Wars and Mexican-American Wars, which provided the opportunity for settler men to reinvent and affirm their masculinity (Smith 2021). Out of this period came the archetype of the Anglo-American Cowboy, an appropriation of Mexican vaquero culture facilitated by the end of the Mexican-American War and a flood of White colonizers in land previously occupied by Mexico (Smith 2021). While real-life cowboys were often Black, Indigenous, and working class, the Anglo-American Cowboy as a mythic figure was not (Berry 2022; Moskowitz 2006; Smith 2021).

Perhaps one of the most famous admirers of the Anglo-American Cowboy was Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt was an Eastern, elite politician, encapsulating the very traits that signaled the waning masculinity of the time (Berry 2022). He aligned himself with the new ideal of masculinity by evoking the archetype of The Cowboy, rancher, and Westerner surrounding his outdoor adventures and trips to the West (Berry 2022). For Roosevelt, the West was a place where patriarchal authority could be reestablished. The land’s supposed emptiness provided space for the Eastern aristocracy to venture, prove their masculinity, and return home to positions of power (Berry 2022). This perspective extends to his creation of the United States Forest Service, where a perceived empty, pure land could be “protected” for Eastern masculine adventures, “frontier clubs,” ranchers, and forestry (Berry 2022). In this way, the “American frontier” might be preserved for future generations to experience the raw wildness of the West long after it had been settled (Berry 2022). Roosevelt advocated for removing Indigenous people from the West and characterized them as refusing to settle the wilderness or engage with land “appropriately.” Reflected in Roosevelt’s attitude about the West is a notion of the “purity” of the frontier (Berry 2022). The frontier became a “laboratory of gender” wherein colonial masculinity is (re)produced through violence against Indigenous, Black, and queer people, women, and land (Berry 2022; Smith 2021). It was also a space where masculinity could assert itself as natural while it mapped itself onto a perceived “natural world” free from the pollution of urbanity (Smith 2021).

Jennifer Moskowitz draws parallels between the mythic figures of the American Cowboy and the English Knight of the Middle Ages. Both figures stem from countries moving towards nationalism, industrialism, and capitalism. Moskowitz explains R.W.B Lewis’ concept of The Cowboy as the “American Adam,” an archetypal figure representing an essentialized American soul, seen as selfless, stoic, and birthed on American soil (Moskowitz 2006). The mythic Cowboy is a figure deeply intertwined with the logics of colonialism, capitalism, and nationalism. Moskowitz theorizes The Cowboy as a nationalistic figure because of his imagined relationship to land (Moskowitz 2006). The Cowboy exists in a supposed neutral space of the Western Frontier, creating nationalist sentiment and movement through the concept of westward expansion. The Cowboy, and the West at large, was a space where the American consciousness could create new memories and understandings through a “collective amnesia” to produce the unity needed to imagine a nation (Moskowitz 2006). The Cowboy furthered the logics of capitalism, colonialism, and extraction as a figure characterized by his simultaneous self-sufficiency, independence, and stoicism, as well as his ability to domesticate both himself and the very land he inhabited (Moskowitz 2006). The figure of The Cowboy links developments of colonial masculinity with both the creation of the American nation and its extractive orientations towards land and Indigenous peoples.

Karuk Masculinity: Indigenous Masculinities as Resistance

Salmon are an integral part of masculinity for the Karuk Tribe, who are located in the Northwest corner of California along the Klamath River (“Impacts” 2022). The tribe is one of the largest in California today, with almost four thousand members and over five thousand descendants (“Impacts” 2022). Although they are recognized by the settler US government, the Karuk Tribe has no reservation, and minimal recognition of hunting, fishing, gathering, and land management rights (Norgaard et al. 2017). For the Karuk Tribe, environmental decline is a form of continued colonial violence and cultural genocide (Norgaard et al. 2017). Since the 1960s, dams have blocked access to 90% of the spawning habitat for spring Chinook salmon and created warm water conditions leading to the growth of cyanobacteria, which limits the oxygen availability in the water for salmon (“Illness” 2022, Norgaard et al. 2017). Policies that prioritize settler wealth over indigenous well-being have prevented indigenous land management practices, allowed excessive extraction of timber, arrested Karuk people for fishing in tribal custom, and diverted water from the Klamath River to farmers in the upper basin (Norgaard et al. 2017). These policies have made Karuk practices increasingly illegal. Tribal leader Leaf Hillman remarks,

In order to maintain a traditional Karuk lifestyle today, you need to be an outlaw, a criminal…it is a criminal act to practice traditional lifestyles and to maintain traditional cultural practices necessary to manage important food resources…If we as Karuk people obey the “laws of nature” and mandates of our Creator, we are necessarily in violation of the white man’s law. It is a criminal act to a Karuk Indian in the 21st century (“Its Illegal to be a Karuk” 2016).

Describing themselves as the “fix the world people,” the Kaurk tribe has had a rich history of tradition, ceremony, and land management practices centered on balance and reciprocity between land and people (“Impacts” 2022). Karuk land management practices are often either in direct conflict with Federal and state laws or are heavily controlled by state agencies like the California Department of Fish and Wildlife and the establishment of the Klamath National Forest (“Impacts” 2022). These policies limit Karuk sovereignty and affect Karuk’s ways of life and relationships with the land.

Salmon are central to Karuk social organization, spirituality, and storytelling. Historically, more than half of the protein and calories in a Karuk diet came from salmon, but forced assimilation has forced the Karuk to rely increasingly less on salmon (Norgaard et al. 2017). For the Karuk people, fish are a gift from Ikxaréeyav, or the First People. Their oral traditions tell the histories of the formation of plants, aquatic animals, and land as gifts to the Karuk to use and manage under the condition of reciprocal care through land management and ceremony (“Píkyav” n.d).

Relationships between the Karuk and the salmon are particularly important for Karuk men, whose gender identities often intertwine with their relationship to the Klamath River and the salmon (Norgaard et al. 2017). This has made the continued degradation of the Klamath River and impacts on salmon particularly harmful. For Karuk men, especially those from fishing families, fishing, participating in ceremonies around fish, and giving fish to their communities are important to ecological, community, and personal health and identity (Norgaard et al. 2017). For many Karuk men, fishing is what makes a man a man. The relationship between masculinity and ecology has meant that colonial control over fishing rights and extractivist histories of water, lumber, and salmon impact Karuk men’s ability to perform ceremonies and rites of passage and fill traditional gender roles within their communities.

Central to Karuk men’s relationship with the salmon is reciprocity and responsibility to community. The relationship between tribe and fish is not extractive but reciprocal. Leaf Hillman, the director of the Karuk Department of Natural Resources, said that,

We [the Karuk people] believe that we were put here in the beginning of time, and we have an obligation, a responsibility, to take care of our relations, because hopefully, they’ll take care of us. And it’s an obligation that we have, and so just like—we say, well, we have to fish. They say, “Well, there aren’t that many fish this year, so I don’t think you should be fishing.” That is a violation of our law. Because it’s failure on our part to uphold our end of the responsibility. If we don’t fish, we don’t catch fish, consume fish… then the salmon have no reason to return. They’ll die of a broken heart” (Norgaard et al. 2017, 103).

Many Karuk men express this same sense of failure associated with no longer being able to consistently provide salmon to their families, communities, and elders, but also with the damaged health of the salmon (Norgaard et al. 2017). The loss of salmon is a piece of what Kari Marie Norgaard, Ron Reed, and J. M. Bacon call “colonial ecological violence,” where continued colonial legacies impede on Indigenous sovereignty, land, and relationship in what constitutes cultural genocide (Norgaard et al. 2017). This crisis of masculinity is, of course, intertwined with continued histories of colonialism, racism, and genocide.

Karuk masculinity, like any other form of masculinity, is not static. In the face of changing possibilities of masculinity related to salmon, some Karuk men have reconstructed masculinity through environmental activism aimed at dam removal and work through the tribal fisheries program (Norgaard et al. 2017). One man described activism and speaking up for the fish as what his role as a fisherman has evolved into:

Before, it wasn’t easy. Ceremonies, subsistence, those, you know, those aren’t easy things to accomplish. There’s a great deal of responsibility and pride involved in those activities, but we never had to go speak for the fish, we never had to go talk about our values, our cultural ways, our traditional values. As long as we followed them, we were taking care of them. But now, the fisherman’s role is also to speak for the fish. Speaking publicly isn’t a common trait of the Karuk people. The people who speak on behalf of the fish or resources are people that have taken that responsibility and have been able to speak for the resource in a way that is foreign to us… I decided to start speaking on behalf of the fish. On behalf of the fishermen. On behalf of the basket weavers, on behalf of the people who walk before us, and on behalf of the people who walk after us. That’s the fisherman today. It’s a burden, it’s a responsibility, it’s what I cherish, and I wouldn’t do anything else. I mean, this is, God put me, the Creator put me on this earth for a reason. I think I’m fulfilling that reason. That’s what it is to me being a fisherman today (Norgaard et al. 2017, 108-109).

For Karuk men, mending ecological damage and traditional masculine gender identity is linked to resisting white supremacy and colonization that infringes on Karuk land sovereignty, non-colonial gender system, ceremony, and way of life. Despite Karuk masculinity’s evolution in the face of declining salmon populations, these new forms of masculinity increasingly rely on nature as symbol more than as material (Norgaard et al. 2017). Karuk masculine identities that are constructed around activism and advocacy in recent years are a reaction to attacks on their way of life stemming from colonization. One Karuk man explained the anxiety tied to the loss of salmon and what it means for the community: “Karuk people actually believe that if salmon quit running, the world will quit spinning, maybe the human race as we know it may be nonexistent… if the river quits flowing, it’s over… if salmon quit running, it’s like the sign of the end” (Norgaard et al. 2017, 107). These evolving forms of masculinity rely on the idea that the salmon will return one day. They emphasize the interdependence between human and non-human beings and focus on caring instead of jeopardizing that relationship.

Colonial Gender: Narrowing and Separation

Land shapes my relationship with humans and other animals in the web of life around me, creating culture and identity. Land shapes language, teaching us what can be said about anything (including gender) and what must remain ineffable. And if we’re starting with land, we need to frame our analysis of gender and sexuality around the fact that the land, and the people who spring from it, are actively being colonized. –Margret Robinson, M’Kmaw Two-Spirit Scholar

Colonial epistemologies narrow masculinity to archetypes that romanticize violence and extraction. Butler’s gender performativity gives insight into how gendered relationships are not created by individuals, but precede the individuals that relate (Butler 2015). Colonial gender narrows the possibility of gendered dynamics along the logics of colonialism. While colonial masculinities often posit gender as biological, hegemonic masculinity theory points to this form of masculinity as not truly singular (as other forms of masculinity are placed under it) but largely aspirational. Colonialism sets an idealized form of gender, the Anglo-American Cowboy, or other variations of mythic figures, which are both inaccessible (in that they are hard to obtain and mythical) and set as natural.

Across American history, colonial masculinity has re-asserted itself to maintain colonial control of marginalized people and land. The mythic Anglo-American Cowboy encapsulates this dynamic. The Cowboy is an aspirational figure who conquers the wild, raw West for the nation. While The Cowboy, in its mythic form, does not accurately represent any individual man, its symbolism allows men like Roosevelt to tap into a romanticized version of violent masculinity. While real-life cowboys were often marginalized peoples, the mythic Cowboy as an imagined figure encapsulated both rugged manliness and the power to domesticate land along the logics of the nation. With its appearances in novels, art, speeches, and other media projects, The Cowboy could create mythic memories, a singular heroic figure painted as the forefront of the project to settle the West (Moskowitz 2016). This is explained by Whitebear’s idea of settler colonialism, where The Cowboy, and thus the imagined White, masculine heroic figure, is positioned as the pinnacle of manhood, shaping land, mindsets, and systems into the logics of the European settler over Indigenous modes of gender and relationship to land (Whitebear 2020).

Whitebear’s description of settler colonialism mirrors Lugones’ insights on the coloniality of gender. Lugones explains how enlightenment ideals of “rationality” posit a singular way of knowing that overwrites Indigenous gendered relationships to land and posits a singular mode of masculinity conceptualized as natural, true, and unchanging (Lugones 2016). Gender expressions that deviate from the values of colonial masculinity, especially those that are non-binary, matriarchal, or non-monogamous, fall into Lugones’ “dark side” of the colonial gender system and are either conceptualized as “lesser” forms of masculinity or are pathologized and thus to be eradicated, assimilated, or shunned (Lugones 2016).

Colonialism’s narrowing of gender possibilities is demonstrated in both Lang’s descriptions of gendercide on non-binary gender systems and the settler government’s engagements with the Karuk Tribe. Lang describes violent assimilation and killings of genders and gender systems which demonstrated Indigenous values of transformation, duality, and change (Lang 2016). Through violence, the logics of colonialism attempt to narrow the possibility of gender expression to fit its values of separation, hierarchy, and singularity. Similarly, colonial policies that prioritize settler profit and criminalize Karuk land management and ceremony narrow the possibilities of how Karuk men are able to express their masculinity.

Despite colonial gender’s insistence on singularity, monomyths are always false. Langs’ insights into Indigenous gender systems, which often allowed for, or were based on, ambiguity, duality, reciprocity, and transformation, point to the ability of gender systems to differ from the logics of colonialism (Lang 2016). Karuk masculinity demonstrates a version of masculinity that deviates from colonial masculinity in that its expression is not violent or hierarchical but instead reciprocal. Central to the Karuk worldview are the ideas of connection between land and body present in Whitebear’s descriptions of Indigenous feminisms and cuerpo-territorio. For the Karuk Tribe, violence against land and people is intertwined not only through parallel logics of extraction from settlers (e.g., control over land and people for profit, extraction, control, and power) but also in that violence against one is ultimately violence against both. Karuk cultural histories and well-being are intertwined with the health of the salmon, and the health of the salmon is intertwined with the health of the Karuk people. The decreasing health of the salmon population within the Klamath River is an example of how the logics of colonialism and its associated gender practice impact both Indigenous peoples and land. Roosevelt’s very US Forest Service has impacted the Karuk tribe, where Karuk land management practices are increasingly criminalized in the name of both White profit (e.g., the prioritization of White industry extracting gold, timber, and fish) and supposed efforts to protect salmon by restricting Karuk access to traditional ceremony, food, and land sovereignty (Berry 2022; Norgaard et al. 2017). In this way, Karuk masculinity deviates from colonial masculinity in that continuing cultural ceremony, land sovereignty, and reciprocal relationships with fish and land are not extractive or violent but a form of resistance.

Even colonial masculinities are not singular or static. The nineteenth century’s crisis of masculinity reveals colonial masculinities’ vulnerability, fluidity, and transformation. This was demonstrated by the need for the construction of The Cowboy as a political tool to enforce the political power of Eastern figures like Roosevelt, whose masculinity was otherwise vulnerable to a perceived “softening” of elite patriarchal power. The ability for a mythic figure to be constructed demonstrates both the fragility of colonial masculinity and that of the nation that it aimed to create.

Part of the violence of colonization is the separation of humans from each other and from land. Butler’s gender performativity theory gives insight into the connection between “gendering” and “humanizing.” Agency is given only to those who conform or aspire to masculinity, power, and individuality as represented by the ideal of the Anglo-American Cowboy. Those seen as parts of “the dark side” of colonial gender endure rhetorical pathologization and violent assimilation as demonstrated by the gendercide of flexible Indigenous genders and sexualities (Lang 2016; Lugones 2016). In the logic of colonial masculinity, to be a man is to become human, and “becoming human” rests on a particular relationship to land: differentiated and extractive.

Conclusion: What do we do with masculinity?

Colonialism has narrowed the mythic possibilities for masculinity, where idealized forms of masculinity, like that of the Anglo-American Cowboy, are rooted in separation from land, extraction, profit, and violence. This limitation can make masculinity feel hopeless, as alternative modes of masculinity are pathologized and shamed or situated within a mythic past. However, the clear construction of the Anglo-American Cowboy gives insight into the vulnerability of this form of masculinity and challenges its truth and strength. Karuk masculinity shows the possibility of an alternative masculine ideal rooted in reciprocity, care, connection, and community. Karuk masculinity would not be appropriate as a universal masculine ideal as it is culturally and geographically specific. However, Karuk insights into an alternative mode of relating to gender give hope both to the possibility of alternative masculinities and a masculinity based on connection as opposed to separation from communities, land, women, etc.

The insidious power in the colonial gender system is its ability to condense possible masculine expressions along the logics of extractivism. Cuerpo-territorio and Indigenous feminisms give insight into the patriarchal nature of colonialism, where in order to justify the extractivism of land and bodies, settlers must separate themselves from the more-than-human. Modes of masculinity stemming from these logics, therefore, are inherently separating. While condemning the modern/colonial gender system’s inherent ties to extractivism, separation, and colonialism is essential, condemning what can appear to be a singular, all-encompassing masculinity can leave a void of possibility, unintentionally playing into colonial masculinity’s tendency to create a false perception of singularity. This is what Sophie Strand refers to as treating masculinity with antibiotics, which only leaves room for pathogens to grow (Strand 2022). Instead, she argues, we should flood colonial masculinities with a biodiversity of alternative masculinities.

Crucial to Indigenous feminisms, Whitebear suggests, is the ability to imagine a liberated future (Whitebear 2020). While logics of colonization rewrite masculinity as singular and unchanging, decolonization is and always will be possible. When the logics of colonization leave us feeling separated from our gendered identities and human and more-than-human communities, we might return to the idea that this separation is an illusion. Philosopher Bayo Akomolafe reminds us that colonization draws false boundaries and that these boundaries can only be healed if we allow ourselves to lose our way to deviate from the monomyth of colonial masculinity.

In ironic ways, decolonizing ourselves is about recognizing the wounds of the conquering imperative, and taking up arms no longer, but limbs that bind us together in an entangling mutuality – for the first cut of the colonizing sword was what cast us – colonizer and colonized, human and nature – asunder…into unbridgeable categories governed by fear and distrust. The healing balm is that which restores our faith that we are held in each other, and by the magic of a world that will not be silenced. Decolonizing ourselves must proceed not by trying to return to a pure image of what it means to be indigenous (an image that may no longer be true), or by trying to erase the lasting marks on our bodies that have been made by colonial incursions and new affectations, but by straying freely and losing our way generously – making kin with the places that hold us, and abiding with the troubling flow of worlding practices that bind us to those who have violated us (Akomolafe, 2015).

Bibliography

Akomolafe, Bayo. “Decolonizing Ourselves.” • Writings – Bayo Akomolafe, August 17, 2015. https://www.bayoakomolafe.net/post/decolonizing-ourselves.

Arcangelis, Carol Lynne, and Lorna Quiroga. “Cuerpo-Territorio:” Revista Eletrônica da ANPHLAC 23, no. 35 (2023): 150–74. https://doi.org/10.46752/anphlac.35.2023.4140.

Berry, Cameron. “Hunters, Cowboys, and Eco-Saboteurs: The Literary Heroes That Turned Wilderness Conservation into an American Political Mythology.” Thesis, Wesleyan University, 2022.

Butler, Judith. “Introduction.” Introduction. In Bodies That Matter, 1–23. London: Routledge, 2015

“Chapter 2: ‘Its Illegal to Be a Karuk Indian in the 21st Century.’” Karuk Climate Change Projects, June 21, 2016. https://karuktribeclimatechangeprojects.com/chapter-2-its-illegal-to-be-a-karuk-indian-in-the-21st-century/.

Chayne, Kamea, and Sophie Strand. “Sophie Strand: Rewilding Myths and Storytelling (EP365).” Green Dreamer, September 29, 2023. https://www.greendreamer.com/podcast/sophie-strand-the-flowering-wand.

Connell, R. W., and James W. Messerschmidt. “Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept.” Gender and Society 19, no. 6 (2005): 829–59. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27640853.

“Illness and Symptoms: Cyanobacteria in Fresh Water.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, May 2, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/habs/illness-symptoms-freshwater.html#:~:text=Fish%20and%20aquatic%20animals,may%20directly%20kill%20the%20animals.

“Impacts of Climate Change on the Karuk Tribe.” Oehha.ca.gov, 2022. https://oehha.ca.gov/climate-change/epic-2022/impacts-tribes/impacts-climate-change-karuk-tribe.

Lang, Sabine. “Native American Men-Women, Lesbians, Two-Spirits: Contemporary and Historical Perspectives.” Journal of Lesbian Studies 20, no. 3–4 (2016): 299–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2016.1148966.

Lugones, Maria. “The Coloniality of Gender.” The Palgrave Handbook of Gender and Development, 2016, 13–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-38273-3_2.

Moskowitz, Jennifer. “The Cultural Myth of the Cowboy, or, How the West Was Won.” Americana 5, no. 1 (2006). https://doi.org/https://americanpopularculture.com/journal/articles/spring_2006/moskowitz.htm.

Norgaard, Kari Marie, Ron Reed, and J. M. Bacon. “How Environmental Decline Restructures Indigenous Gender Practices: What Happens to Karuk Masculinity When There Are No Fish?” Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 4, no. 1 (2017): 98–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332649217706518.

“Pikyav Field Institute.” Karuk Tribe Official Website. Accessed December 18, 2023. https://www.karuk.us/index.php/departments/natural-resources/eco-cultural-revitalization/pikyav-field-institute.

Smith, Rick W. “Imperial Terroir.” Current Anthropology 62, no. S23 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1086/711661.

Strand, Sophie. The flowering wand: Rewilding the sacred masculine. Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions, 2022.

Whitebear, Luhui. “Disrupting Systems of Oppression by Re-Centering Indigenous Feminisms.” Persistence is Resistance Celebrating 50 Years of Gender Women Sexuality Studies, August 12, 2020. https://uw.pressbooks.pub/happy50thws/chapter/disrupting-systems-of-oppression-by-re-centering-indigenous-feminisms/.