9 “Sure Got to Prove it On Me”: Queer Feminist Legacies in Gertrude “Ma” Rainey’s Blues

Queer Feminist Legacies in Gertrude “Ma” Rainey’s Blues

aecf2022

Arenaria Cramer

Introduction

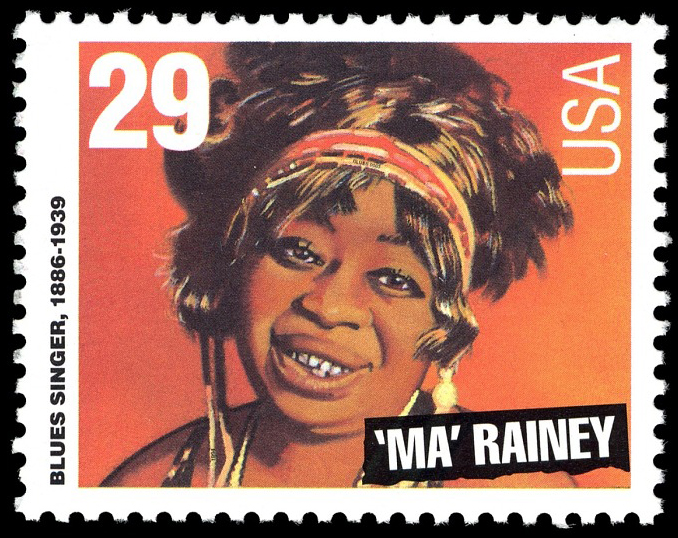

Inducted into the Blues Foundation’s Hall of Fame in 1983, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1990, with a song inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 2004, and with a commemorative postage stamp in her honor, Gertrude “Ma” Rainey is widely regarded as a pioneer of the genre. Subverting almost every racial, heteronormative, class-based expectation imposed upon the Black woman in the turn-of-the-century American south, Rainey rose from a minstrel act in rural Alabama to widespread fame by the 1920’s; in the process, she defined the Blues as they are known today. With her vocal skill, her lyrics, and her larger-than-life stage personality, Ma Rainey forwarded many of the expressions of Black feminist consciousness which would not be examined or articulated in art or literature until much later.1

Smithsonian National Postal Museum. “The ‘Ma Rainey stamp was issued September 17, 1994. 2

The privilege of hindsight allows even the most mainstream academic literature today to appreciate the dissonances between Rainey’s on-stage attitude and lyrics and the image of her forwarded by Paramount pictures. In an industry that elevated Black female artists purely because they had proven to be the most profitable demographic, Rainey leveraged the consumerist fervor surrounding minstrel shows and a Vaudeville aesthetic to express the ideals and struggles of the poor Black woman in the American south. In this leveraging, Rainey handled themes of motherhood, explicit sexuality, and political protest constantly. The cultural phenomenon of Rainey’s Blues combines the slave spiritual, the Minstrel’s performance, and the African Oral Tradition, fostering a black working-class social consciousness on a historic scale.3

I argue in this chapter that Rainey’s lyrics and performances hint at and engage with elements of Queer Black Feminist theory, even as her recordings were so carefully monitored and censored by the white and patriarchal recording industry. Rainey forwarded the pursuit of agency and self-determination for queer Black women in her navigation of the industry and the publicity that accompanied her musical fame. Following in the footsteps of the earliest Black American feminists, such as Sojourner truth, she developed Black feminist thought in her quotidian rebellion against the discrimination and subjection that every black woman in early twentieth century America regularly faced. While she did not label her actions or social position in the theoretical terms since developed for such resistance, Rainey utilized, at least in part, her own version of the theoretical lenses that have since been further developed by Audre Lorde, the Combahee River Collective, and Kimberlé Crenshaw.4 While activist and theorist Angela Davis has credited early American blues stars with developing many aspects of early black feminism, I continue her work by drawing a through-line from Sojourner Truth to present-day feminist theory. I do not argue that Rainey “did Black feminism first,” as such an approach would be both reductive and deterministic; rather, I situate Ma Rainey and her influences on American popular culture as key contributors to a queer Black feminist tradition that existed long before, and continues long after, the peak of blues popularity in the US.

Rainey was an impressive figure in almost every regard, subverting racialized and gendered expectations of her at almost every opportunity and defining the blues as we understand them today/ this paper limits its scope to a few specific scenes in her extraordinary life. By illuminating some of Rainey’s works that are most relevant to modern feminist thought, I build my analysis on a foundation rooted deeply in Rainey’s own words and ideas. I see this methodology as essential to any study of Black women in the public eye; popular media rarely afforded them a platform to speak freely, so their art and their lyrics became the only mode of expression that could speak directly to their working-class Black audiences. As I examine the overtly homosexual themes of Rainey’s lyrics, her textual themes of motherhood, her take on the universal experience of the American Black woman, and her subversive stage presence, I trace a Black Feminist tradition through Rainey’s words, actions, and aesthetic as they challenged the hierarchies of the industry and society within which she operated.

Ma Rainey and her band. 5

Analytical Framework: Feminist Theorizing From Truth to Crenshaw

Rainey’s feminism grew from a tradition of resistance and survival in the post-slavery American South. The racialized and gendered institution of American Chattel Slavery afforded precious few enslaved women the opportunity to speak freely about their experiences of enslavement, let alone to record or broadcast their personal philosophies as they developed them. One notable exception to this is Sojourner Truth, a freed slave, a spiritual leader, and abolitionist. In 1851 she delivered her famous speech, “Ain’t I a Woman”, at the Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio.6 An indictment of the differential treatment of white versus Black women, the speech calls on the white women at the convention––a vast majority–– to consider Black women as not just human, but human women, in their fights for equal treatment of the sexes. Truth’s biblical rhetoric and the common experience of motherhood to build a bridge between her own experiences as an enslaved woman and those of condescending white women at the convention, asserting that “I have borne thirteen children, and seen most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother’s grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain’t I a woman?”7 With this question, as well as with her abolitionist actions, Truth established herself as one of the earliest Black American feminist theorists.

Having established female Blues singers as essential contributors to a black radical feminist tradition, my theoretical framework now temporarily skips over a century to the words of the Combahee River Collective. Active in Boston, Massachusetts from 1974 to 1980, the collective was a Black lesbian feminist socialist organization which argued that both the white feminist movement and the Civil Rights Movement had failed to address their needs as Black women and more specifically as Black lesbians. In their 1977 statement, the collective focuses on the genesis of contemporary Black feminism, arguing for the relevance of the Black Lesbian perspective in a feminist or civil right struggle, with an emphasis on identity politics as they “believe that the most profound and potentially the most radical politics come directly out of our own identity, as opposed to working to end somebody else’s oppression.”8 The collective focused on the sexual politics of queer Black women as they sought to construct a revolutionary politics of liberation, asserting a belief that “sexual politics under patriarchy is as pervasive in black women’s lives as are the politics of class and race.”9

I will also draw upon Audre Lorde’s 1978 theorization of the erotic in my discussion of Rainey’s treatment of pleasure and sexual freedom. In the context of a discussion of pornography, Lorde asserts that “the erotic is not a question only of what we do; it is a question of how acutely and fully we can feel in the doing.”10 Beyond sexual liberation, Lorde argues that by reclaiming joy and feeling in their endeavors, women––and specifically black Lesbian women–– can meaningfully challenge the fear and repression they face in racist, patriarchal, and anti-erotic American society. Lorde’s writings, as well as those of the Combahee River Collective, are critical to understanding the ramifications of Rainey’s openly homosexual presentation in later twentieth-century discourse surrounding sexuality and the place of the lesbian within a Black Feminist movement.

The most recent Black Feminist literature upon which my paper will draw is Kimberlé Crenshaw’s “Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color.” Now a seminal text of Black Feminist theory, Crenshaw’s 1993 paper described the complexities that arise at the intersections of feminist and anti-racist struggle, specifically in the Black American Community’s resistance to carceral and police violence. In this early work, Crenshaw elaborated on the intersectional inequities of the U.S. criminal justice and expertly explained the multiply oppressive effects of racism and sexism on Black women. In her discussion of culturally nonconforming women’s increased likelihood of being devalued by the legal system in the case of their sexual assault, she concluded that Blackness is regarded by dominant society as cultural deviance enough to lower a woman’s value and to justify rape in the eyes of the legal system. Crenshaw focused on “identity politics,” arguing that rather than ignoring differences of identity (socially constructed as they may be), antiracist and antisexist movements must recognize that “identity politics takes place at the site where categories intersect” and embrace Intersectionality as a framework for constructing group politics.11

As I have outlined them above, black Feminist theorizations of womanhood, queerness, the erotic, and intersectionality will guide my interpretation of Rainey’s lyrics and performance practices. Though I work chronologically, placing Rainey’s influence on Queer Black Feminist thought as a continuation of Sojourner Truth’s work and a precursor to black queer feminist work of the late twentieth century, I reject a linear historiography of these movements and the theories they drew upon. Only an unforgivably oversimplified history of Queer Black Feminist organizing in the US would understand these theories as evolving in the sense that their earlier articulations and applications were somehow less complex or developed; to give credit where it is due and to appreciate the long history of Black feminist organizing in the US is to hold dualities of queer and not queer, public and private, modern and age-old as we trace radical feminist thought through the post slavery American south.

Gertrude “Ma” Rainey becomes the Mother of the Blues

Gertrude Pridgett was born in the late 1880’s, the second of Thomas and Ella Pridgett’s five children. Her exact date and place of birth remain unknown, but the family likely lived in either Russel County, Alabama, or Columbus, Georgia. In her early teens, Pridgett began performing in various Black minstrel shows, gaining her stage name after marrying William “Pa” Rainey in 1904. The Blues were rapidly gaining popularity and, by 1914, the Raineys were a relatively well-known act. In the late 1910s, with the new accessibility of recordings, demand for recordings by Black musicians was on the rise. In 1923, Paramount Records producer J. Mayo Williams “discovered” Rainey, and over the next five years Rainey produced more than 100 recordings. Paramount marketed her extensively, dubbing her the “Mother of the Blues”, the “Songbird of the South”, the “Gold-Neck Woman of the Blues” and the “Paramount Wildcat.”12 Rainey toured across the country, playing with Louis Armstrong and other prominent Blues musicians. At the peak of her career, Rainey generated up to $350 per week on tour; her voice, songwriting, and performance skill captivated black and white audiences alike.13

Unlike many blues singers of her time, Rainey wrote at least one third of the songs she sang. Her lyrics illuminated Black American life for a widespread audience as Vaudeville and Blues gained popularity throughout the 1920’s. They dealt with themes of injustice and melancholy, the blues themselves a figurative expression of all that kept Black people poor, tired, down-and-out. For the Black women who pioneered the genre, the blues could be brought about by white culture, economic hardship, disloyal partners, and the like. Even and especially in her melancholy performances and ‘moaning’ vocal techniques, Rainey’s blues took on an attitude of defiance. Covering themes of sexual freedom, romantic agency, and self-determination, Rainey’s experiences as a Black woman in the American south, only one generation removed from slavery, resonated with her audience of tired, working-class, mostly Black Americans in the advent of the recorded song.14

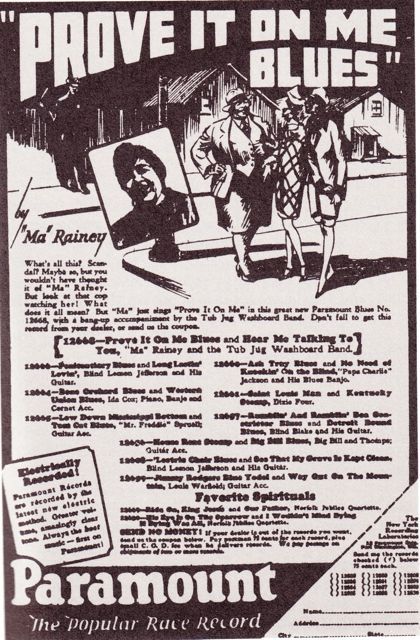

As she rose to fame, Rainey grew close with Bessie Smith, a younger blues singer who would go on to become the most popular female blues singer of the 1930s. In 1916, Rainey separated from her husband, and in 1925 she was arrested at a lesbian bar in Harlem. The following morning, Bessie Smith bailed her out of jail. The two were part of a broader circle of lesbian and bisexual Black women in Harlem.15 In 1928, Rainey recorded “Prove It on Me” Blues,” an unapologetic claim to her lesbian identity. The sing tells Rainey’s side of the story: from her point of view, the police were the least of her concerns; Rainey’s lyrics concern only the girl she came with.

Prove It on Me Blues

Went out last night, had a great big fight

Everything seemed to go on wrong

I looked up, to my surprise

The gal I was with was gone.

Where she went, I don’t know

I mean to follow everywhere she goes;

Folks say I’m crooked.

I didn’t know where she took it

I want the whole world to know.

They say I do it, ain’t nobody caught me

Sure got to prove it on me;

Went out last night with a crowd of my friends,

They must’ve been women, ‘cause I don’t like no men.

It’s true I wear a collar and a tie,

Makes the wind blow all the while

Don’t you say I do it, ain’t nobody caught me

You sure got to prove it on me.

Say I do it, ain’t nobody caught me

Sure got to prove it on me.

I went out last night with a crowd of my friends,

It must’ve been women, ‘cause I don’t like no men.

Wear my clothes just like a fan

Talk to the gals just like any old man

Cause they say I do it, ain’t nobody caught me

Sure got to prove it on me.16

Many of Rainey’s lyrics hinted at or openly embraced homosexuality, both lesbian and gay. Her “Sissy Blues” openly discuss gay men in the Black community:

Sissy Blues

I dreamed last night I was far from harm

Woke up and found my man in a sissy’s arms

“Ah, hello, Central, it’s ’bout to run me wild

Can I get that number, or will I have to wait a while?”

Some are young, some are old

My man said sissy’s got good jelly roll

“Ah, hello, Central, it’s ’bout to run me wild

Can I get that number, or will I have to wait a while?”

My man’s got a sissy, his name is Miss Kate

He shook that thing like jelly on a plate

“Ah, hello, Central, it’s ’bout to run me wild

Can I get that number, or will I have to wait a while?”

Now all the people ask me why I’m all alone

A sissy shook that thing and took my man from home

“Ah, hello, Central, it’s ’bout to run me wild

Can I get that number, or will I have to wait a while?”

Feminist theory in Rainey’s Lyrics

Though Sojourner Truth gave her “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech almost seventy years before Ma Rainey became famous, many of Rainey’s lyrics allude to a tradition of Black feminism praxis under conditions of enslavement. Central to Truth’s shrewd analysis is the theme of labor; as she fought the institution of slavery, she developed a keen understanding of racialized labor systems, which allowed her to see the flaws in a woman’s movement that only fought for the equality of white women. Being helped into carriages and lifted over ditches, she explains, is one aspect of the patriarchal strategy of gendered oppression. Truth’s argument for solidarity between white feminists and an anti-slavery movement thus constituted an early intervention in racially conscious feminist discourse.

Rainey’s lyrics grew from this discussion, as blues grew from field hollers and a culture of resistance during slavery. Many of Rainey’s lyrics celebrated Black working-class people, with themes of labor and class arising out of direct reference to slavery:

Slave to the Blues

Ain’t robbed no bank, ain’t done no hangin’ crime

Ain’t robbed no bank, ain’t done no hangin’ crime

Just been a slave to the blues, dreamin ’bout that man of mine

Blues, please tell me do I have to die a slave?

Blues, please tell me do I have to die a slave?

Do you hear me pleadin’, you going to take me to my grave

I could break these chains and let my worried heart go free

If I could break these chains and let my worried heart go free

But it’s too late now, the blues have made a slave of me

You’ll see me raving, you’ll hear me cryin’

Oh, Lord, this lonely heart of mine

Whole time I’m grieving, from my hat to my shoes

I’m a good hearted woman, just am a slave to the blues.17

In this example, the blues are personified as a kind of specter, a legacy of slavery that haunts the Black community. In this and other songs, Rainey specifically discusses the gendered dynamics in the black community of post-slavery south.18 Rainey and Truth’s critiques, taken together, tell an early story of Black feminist thought as it theorized gender in terms of class.

Rainey’s feminist blues further challenged dominant patriarchal expectations in their engagement with themes of deviant sexuality. Rainey’s songs openly handle themes of lesbian sexuality. In 1928, after her arrest in Harlem, Rainey’s release of “Prove it On Me Blues” put the burden of proof on the police and those who would dare express concern with Rainey’s intimate relationships. It is worth quoting Hazel Carby’s analysis that Rainey’s “Prove it on me Blues” “vacillates between the subversive hidden activity of women loving women with a public declaration of lesbianism. The words express a contempt for a society that rejected lesbians… But at the same time the song is a reclamation of lesbianism as long as the woman publicly names her sexual preference for herself.”19 Taken together, Rainey’s lesbian identity and her sexually ambiguous—if not overtly homosexual—lyrics bring the intricacies of sexuality and presentation into her performance of femininity and her feminist critiques. Almost fifty years later, the Combahee River Collective would proclaim their continued commitment to the Black Feminist struggle, stating that “We believe that sexual politics under patriarchy is as pervasive in black women’s lives as are the politics of class and race.”20 While the Combahee River Collective formed within the context of the Civil Rights movement and thus had the momentum and language to articulate this intersection more explicitly, it reads with a self-awareness of its situation within a long history of black feminist radical thought.

More broadly than her engagement with queer sexuality specifically, Rainey’s blues reclaimed sexual agency and romantic self-determination for the working-class Black woman.

Using Lorde’s language, we can understand the erotic as a space of joy and freedom through which the woman—and specifically the black woman—can desire and seek her own pleasure. Rainey’s blues speak to the erotic more explicitly than they do perhaps any other modern feminist theory. Her lyrics frequently engaged (in fact, they defined) the typical blues themes of the scorned woman, an unfaithful man, hard times, and so on. But Rainey’s lyrics hardly express a dejected hopelessness in the face of these hardships; instead, they celebrate independence and the strength of the Black woman to choose her own life, relationships, and path. In her book Blues Legacies and Black Feminism, Angela Davis reflects that

The blues songs recorded by Gertrude Rainey and Bessie Smith offer us a privileged glimpse of the prevailing perceptions of love and sexuality in post-slavery black communities in the United States. Both women were role models for untold thousands of their sisters to whom they delivered messages that defied the male dominance encouraged by mainstream culture. The blues women openly challenged the gender politics implicit in traditional cultural representations of marriage and heterosexual love relationships. Refusing, in the blues tradition of raw realism, to romanticize romantic relationships, they instead exposed the stereotypes and explored the contradictions of those relationships. By so doing, they redefined women’s “place.” They forged and memorialized images of tough, resilient, and independent women who were afraid neither of their own vulnerability nor of defending their right to be respected as autonomous human beings.21

With her lyrics, her commanding stage presence, and her openly queer sexuality, Ma Rainey evoked the erotic in every dimension Lorde later describes. In her “prove it on me Blues”, for example, Rainey dwells not on the stress or injustice of her run-in with the New York police, instead focusing on the relationships that were harmed by it (specifically the one with her “gal”). This retelling of events allowed Rainey to tell her side of the story when media and Paramount’s marketing team would not elevate her voice if it wasn’t singing.

Ma Rainey, “Prove It On Me Blues,” Advertisement. 1928, Queer Music Heritage, JD Doyle Archives.

Lastly, as it addressed all Black Americans, Rainey’s feminism was acutely aware of the intersections between gendered and racialized violence as they compounded to limit Black Women’s freedom. Her lyrics frequently dealt with themes of domestic violence, often with the woman taking up arms in self-defense.

Cell Bound Blues

Hey, hey, jailer, tell me what have I done?

Hey, hey, jailer, tell me what have I done?

You’ve got me all bound in chains, did I kill that woman’s son?

All bound in prison, all bound in jail

All bound in prison, all bound in jail

Cold iron bars all around me, no one to go my bail

I’ve got a mother and father livin’ in a cottage by the sea

Got a mother and father livin’ in a cottage by the sea

Got a sister and brother, I wonder do they think of poor me?

I walked in my room the other night

My man walked in and begins to fight

I took my gun in my right hand

Told him, folks, I don’t wanna kill my man

When I said that, he hit me ‘cross my head

First shot I fired, my man fell dead

The papers came out and told the news

That’s why I said I got the cell bound blues

Hey, hey, jailer, I got the cell bound blues22

This song narratively addresses many of the intersectional injustices which Black women faced in the post slavery south: the carceral system’s disruption of the family structure and motherhood, the isolating reality of self-defense for women (especially black women) in situations of domestic violence, and the media’s invasive presence in the Black woman’s life. Rainey’s lyrics artfully represented the nuance of domestic violence within the Black community as well as the causative and often resultant violence of the carceral system and the complexity of intersecting racial and gendered oppression within the American justice system. Many of her original lyrics––that is, what Rainey wrote on lead sheets for live performance –– were censored by producers when Rainey reached the recording studio. Many of these censored verses dealt explicitly with the convict-lease system and the hard manual labor that imprisoned Black men—as well as many Black women–– were pressed into by the profit-driven prison system. Rainey’s Chain gang blues are one such song:

Chain Gang Blues

The judge found me guilty, the clerk, he wrote it down

The judge found me guilty, the clerk, he wrote it down

Just a poor gal in trouble, I know I’m county road bound

Many days of sorrow, many nights of woe

Many days of sorrow, many nights of woe

And a ball and chain everywhere I go

Chains on my feet, padlock on my hands

Chains on my feet, padlock on my hands

It’s all on account of stealin’ a woman’s man

It was early this mornin’ that I had my trial

It was early this mornin’ that I had my trial

90 days on the county road, and the judge didn’t even smile23

In 1993, Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term “intersectionality” to describe precisely this imbrication of oppressions. Writing much later in the twentieth century, Crenshaw focuses much more narrowly on identity politics within the Black feminist movement. Her theories, however, were firmly situated—like Rainey’s—within an American carceral system that targets Black men, cyclically inflicting trauma on Black women.

Popular representations and legacy in the modern day

By the end of the 1920s, the “Classic Female Blues” style was declining in popularity. The great depression struck the vaudeville industry hard, and a new era of solo performers—mostly men—was on the rise. Still, Ma Rainey’s influence reverberated throughout generations of blues and jazz artists. As jazz historian Dan Morgenstern notes, “Bessie Smith (and all the others who followed in time) learned their art and craft from Ma, directly or indirectly.”24 Though the demand for Black women blues singers receded, Ma Rainey’s legacy as a pioneer of the blues was cemented in American popular culture and the social fabric of the working-class Black American.

In recent years, with pressure from social movements and the political left, institutions from academia to Hollywood have embraced the sounds and stories of Black Women. In 2020, Netflix released Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom to critical acclaim. Based on August Wilson’s 1982 play, the movie depicts Rainey’s suspicion of white producers who “only want her voice,” and her assertiveness in the face of discrimination and condescension.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yRyaUcVfhak

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JBEtELYPULk

Perhaps its best feature is the film’s demonstration that Rainey’s true legacy is one of performance. Her stage persona, much like her lyrics and off-stage persona, is unapologetically Black, Working-Class, and a woman. But while marketers profited from the exoticization of her gender non-conforming presentation, southern black women would have understood that Rainey’s expansion of gender roles was typical for the working black woman.25 Rainey sang of hard labor in a deep voice, two things that were entirely unfamiliar to upper-class white suffragist women, though they may have considered themselves feminists. Though she sang of hardship, Rainey’s songs were a celebration of autonomy for the black woman who had had enough. As Rainey developed and popularized classic blues, classic blues developed a Black working-class social consciousness; as Davis states, “[Ma Rainey’s] song’s… foreshadowed a brand of protest that refused to privilege racism over sexism, or the conventional public realm over the private as the preeminent domain of power.”26 In undermining these normative markers of identity as parameters that limit social organizing, Rainey invited Black working class people to expand their solidarity with one another just as she expanded popular conceptions of gender identity and presentation.

Ma Rainey and other blues-singing women of the Classic blues era created a culture of queer self-determination in the most unlikely place of all: the post slavery American south. While Black Queer Feminist theorists and activists would articulate this struggle during and after the protest era of the sixties, Rainey’s lyrics and performance style cultivated a larger-than-life attitude of self-love and shameless pleasure that radically shifted the dynamics of the recording industry and popular media by leveraging the buying power of the Black American working class. While Rainey’s fame is but one chapter in the long story of Radical Black American Feminism, she nurtured that tradition in the reconstruction-era American south. In part, directly or indirectly, much like much later rock and pop music; the work of scholars and activists from Crenshaw to Lorde, from the Combahee River Collective to Angela Davis has all been shaped by Ma Rainey.

Bibliography

Combahee River Collective “A Black Feminist Statement.” Monthly Review 70, no. 8 (2019): 29–36. “A Black Feminist Statement,” 2022.

Abbott, Lynn, and Doug Seroff. The Original Blues: The Emergence of the Blues in African American Vaudeville. American Made Music Series. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2017.

Crenshaw, Kimberle. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review 43 (n.d.).

Davis, Angela Y. (Angela Yvonne). Blues Legacies and Black Feminism: Gertrude “Ma” Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Billie Holiday. New York: Pantheon Books, 1998.

Faderman, Lillian. Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers: A History of Lesbian Life in Twentieth-Century America. New York: Columbia University Press, 1991.

Lieb, Sandra R. Mother of the Blues: A Study of Ma Rainey. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1981. http://www.gbv.de/dms/hbz/toc/ht004707266.PDF.

Lorde, Audre. Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power. Out & Out Pamphlet, no. 3. Brooklyn, N.Y.: Out & Out Books, 1978.

The Smithsonian National Postal Museum Archive. “Ma Rainey.” Accessed December 3, 2023. https://postalmuseum.si.edu/exhibition/the-black-experience-music-blues-singers/ma-rainey.

The Sojourner Truth Project. “Compare the Speeches.” Accessed December 3, 2023. https://www.thesojournertruthproject.com/compare-the-speeches.

Truth, Sojourner, Olive Gilbert, and Cairns Collection of American Women Writers. Narrative of Sojourner Truth, a Bondswoman of Olden Time: With a History of Her Labors and Correspondence Drawn from Her “Book of Life.” The Schomburg Library of Nineteenth-Century Black Women Writers. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991. http://catdir.loc.gov/catdir/enhancements/fy0635/90041024-d.html.

Notes