15 Human Rights Activist (and Martyrs) of México

elizabethpalomaresguzman25

Elizabeth Palomares Guzmán

QWS-183: Queer Feminist Theories

Human Rights Activist (and Martyrs) of México

Introduction:

Daily people with intersecting identities in México are often faced with harassment or violence due being in a society that allows systematic oppression of “lower” class, queer and/or because of their racial identities. Despite all the obstacles faced, people belonging to these communities have managed ways to create resistance against systematic forms of oppression and be able to survive. The achievements and frameworks that queer and feminist activists have created in México need to be recognized to counteract their invisibilization because they are in developing country. In this paper I want to amplify their voice and analyze the ways in which they have created a safe space and community for each other. Additionally, I want to acknowledge all the work and resistance the activists have done, their accomplishments and recognize the martyrs within these movements. The paper will include work from key feminist and intersectionality theorists including Audre Lorde, Gloria Anzaldúa, and Kimberlé Crenshaw. I will be using their theoretical frameworks to analyze the unique challenges faced by activists in Mexico along with other sources regarding what activists have accomplished and the tragedies that have occurred throughout the movement.

Although time passes and there are new people and ideas within movements, we must acknowledge the work that has been done by all the trailblazers. This is the case especially with individuals that, despite their marginalized identities, worked hard to achieve their goals and help their communities. This is why I wanted to include the works of Audre Lorde, Gloria Anzaldúa, and Kimberlé Crenshaw, who in my opinion, have been some of the most influential trailblazers for many communities and liberation movements.

While recognizing these influential trailblazers, I also want to acknowledge those that have fought for their communities but have been silenced, forgotten, subjected to violence, or murdered. Rest in power to all Queer people, feminists, revolutionaries, and victims of systematic oppression and violence everywhere. Most recently, descansa en poder Jesús Ociel Baena, who was Mexico’s first openly non-binary magistrate, the first to obtain a passport with a nonbinary gender marker, and a tireless advocate for LGBTQ+ rights.

Theoretical Framework: Lorde, Anzaldúa and Crenshaw

“The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” – Audre Lorde

Audre Lorde’s essay, “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” helps to understand the foundation for the need for new systems and methods in activism. Lorde argues that existing systems perpetuate oppression and that a collective effort is required to create inclusive spaces for all. This perspective is essential to analyze the activism in Mexico, as it makes us question how activists navigate and challenge oppressive structures unique to their context; especially, since due to México’s unique history, there are numerous factors that are impacting the way socio-economic oppressive systems function. These systems have survived as a legacy initiated by the Spanish Empire and although they have gained their independence the systems have persisted. Along with the impacts of imperialism conducted by the United States to Mexico, leading to Queer people and women life experiences have being determined by colonization and imperialist beliefs.

Throughout her essay, Lorde powerfully critiques the failure of mainstream academic feminism to recognize and embrace differences between women, especially women of color, poor women, and lesbians. As she declares, “Advocating the mere tolerance of difference between women is the grossest reformism.” Lorde argues that simply tolerating differences is not enough – we should see diversity as a creative force, “necessary polarities between which our creativity can spark like a dialectic.” This perspective resonates deeply regarding the context in Mexico, where conservative Catholic viewpoints still dominate much of society. It can be incredibly difficult for more privileged, mainstream Mexicans to truly understand the intersecting struggles of queer people and women. As Lorde might argue, even if an individual is willing to rethink their opinions on socioeconomic inequality, they may cling to oppressive beliefs regarding gender and sexuality. Her analysis suggests that due to the interconnectedness of people’s identities and beliefs, progress for queer and women’s rights has stalled in Mexico. For holistic liberation to occur, there is an urgent need for open, productive dialogue and coalition-building across differences.

Lorde famously argued that “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house” (p. 27). In her view, working within existing oppressive systems will only lead to “the narrowest perimeters of change.” (p. 25) Currently, people endure a society where they are discriminated based on their socio-economic status, race, ethnicity, nationality, sexuality and or their gender identity. To no longer endure the current discriminations, new systems must be created, since “community must not mean a shedding of our differences” and it can ensure the well-being of everyone. With the various types of discriminations impacting people’s lives, people cannot necessarily see each other’s point of view or agree on what would consist of a “new systems.” This is why it is vital for an understanding that everyone is impacted by the same oppressor that created these systems, but just on various levels. This is what activist throughout Mexico have been attempting to explain, especially regarding femicide and LGBTQ+ crimes.

Overall, Lorde calls for embracing differences as a source of creativity and power. Genuine social change requires building new communities and systems that empower marginalized groups, rather than attempting superficial reforms within existing structures of domination. Lorde makes an urgent case that feminists must focus on defining and seeking a new world, not simply working within the current patriarchal paradigm.

La Mestiza Consciousness– Gloria Anzaldúa

Gloria Anzaldúa’s “La Conciencia de la Mestiza” is an important concept for the understanding of the intersectional identities of mestizo individuals, emphasizing the challenges they face in a society that struggles to accept the complexities of being mestizo, a woman, and queer simultaneously. Anzaldúa argued that: “The mestizo and the queer exist at the same time and point on the evolutionary continuum for a purpose. We are a blending that proves that all blood is intricately woven together and that we are spawned out of similar souls,” (107) resonates deeply in understanding the complexity of identities people navigate. By acknowledging the interconnectedness of these aspects, Anzaldúa emphasizes the purpose and strength in the blending of identities, challenging societal norms and advocating for the acceptance of diverse, intertwined existences.

Anzaldúa further explains the gendered dynamics within mestizo communities, highlighting the significance of tenderness and vulnerability: “Tenderness, a sign of vulnerability, is so feared that it is showered on women with verbal abuse and blows. Men, even more than women, are fettered to gender roles. Women, at least, have had the guts to break out of bondage. Only gay men have had the courage to expose themselves to the woman inside them and to challenge the current masculinity,” (106). Here the author highlights the complex struggles faced by mestizo individuals who do not conform to traditional gender roles. Anzaldúa’s work becomes a crucial tool in comprehending the nuances of resistance against societal expectations, providing an understanding of the courage required to navigate and challenge gender norms. This is the case especially in a conservative and religious country such as Mexico, where colonialism has embedded society making anything outside the cis heterosexual, white and/or male norm punished as an anomaly.

In the context of mestizo individuals attempting to survive and resist societal expectations, Anzaldúa’s work serves as empowerment for Queer, women and Latine individuals. Her exploration of the simultaneous existence of mestizo and queer identities disrupts the conventional narratives that seek to escape predefined categories. Those in Mexico, particularly exist in these “borderlands,” embodying unique perspectives due to their multiple identities. By embracing the intertwined nature of these identities, Anzaldúa’s work becomes a source of strength for those navigating the complex intersectionality of being mestizo, a woman, and queer, offering a framework for survival and resistance against a society that often seeks to erase or marginalize existence.

The Concept of Intersectionality – Kimberlé Crenshaw

Kimberlé Crenshaw’s insights on identity politics and intersectionality offer a deeper understanding of femicides and queer violence in Mexico. Crenshaw notes that the problem with identity politics lies not in its failure to transcend difference but rather in its tendency to overlook intragroup distinctions. In the context of violence against women, this oversight becomes problematic because the violence many women experiences is shaped by dimensions like race and class, which are often disregarded. This conflation within identity politics contributes to tension among groups, debilitating efforts to politicize violence against women. Therefore, applying an intersectional lens to the issue becomes crucial for unraveling the multifaceted nature of these challenges and developing interventions that address the nuanced struggles faced by women of color and queer people.

Crenshaw’s observation that women of color find themselves marginalized within discourses shaped to respond to either their gender or their racial identity is particularly relevant to issues in Mexico. The intersectional identity of being both women and of color places them at the periphery of discussions that only acknowledge one facet of their complex identities. This marginalization shows the need to recognize and address the intricacies of violence faced by women in Mexico, acknowledging the interplay of gender, race, and class in shaping their experiences.

Furthermore, Crenshaw’s exploration of how people of color often weigh their interests in avoiding issues that might reinforce distorted public perceptions against the need to acknowledge “intra community” problems is a reflection on the challenges faced in combating femicide and queer violence. For example, although feminist activists are arguing for the right to live in peace, they might not necessarily believe that Queer individuals have a right to also live in peace. This can also occur vise versa, Queer individuals like queer men might not fully comprehend and be allies to fight femicide. The cost of suppressing these discussions goes unrecognized, influencing perceptions of the severity of the problems faced by these communities. By embracing Crenshaw’s framework, we all can navigate addressing public perceptions and acknowledging the intra community issues, ensuring that interventions are inclusive and responsive to the experiences within these marginalized groups in Mexico. Leading to a more comprehensive and holistic tactics to ensure the peace and liberty of many people suffering of oppression.

Indigenous Feminism – Sabine Lang

In “Native American men-women, lesbians, two-spirits: Contemporary and historical perspectives” Lang observes that gender diversity was a widespread trait in Indigenous North American cultures, with institutionalized statuses for “men-women” and “women-men” based on occupational gender roles. She states that “Native people who were considered “deviant” so they were “targeted by missionaries, and other representatives of the dominant non Native society” and used “violence and ridicule” (300) to eventually make them conform to European beliefs. However, traditions accepting those who were neither women nor men disappeared due to colonization. This resulted in marginalization and “triple discrimination” for contemporary two-spirit people as women, lesbians, and Native Americans.

Additionally, Lang documents how in Native cultures, sexuality classifications were based on gender roles rather than biological sex. So some “homosexual” relationships in Western terms were seen as heterogender and sanctioned. With loss of multiple gender statuses, people entered heterosexual marriages but still had same-sex relationships. This complicates assumptions that Indigenous cultures were more accepting of certain expressions of queerness but not homosexuality as defined by settlers. It calls for nuance in how indigenous feminisms reconstitute traditions, ensuring continuity across past and current Queer diversity.

At last, Lang shows how contemporary two-spirit identity blends indigenous spirituality, gender, and sexuality in efforts toward decolonization. The inclusivity of two-spirit builds coalition across LGBTQ and straight Natives sharing trauma under ongoing settler occupation. Though some scholars critique studying only historical roles, Lang argues profoundly spiritual contemporary two-spirits keep traditions alive for community benefit. By there being a priority to maintain Native traditions and a community, demonstrates how important is to recognize the effects of colonization and that once it was possible to openly express ourselves; and one day people will be able to do freely.

The Context: Brief Colonial Mexican History and Impacts

In 1519, Hernán Cortés, a Spaniard conquistador, landed in present day Veracruz and led an expedition to “discover” the “new” land as part of the colonization process Christopher Columbus initiated in the Caribbean in 1492. Two years later, Cortés and Spaniard soldiers conquered Mexico and the colonization of people and land began. For three hundred years, Mexico remained as a Spaniard colony and throughout the whole territory the Spanish Crown propagated and forced Catholic beliefs, racism, and colorism, in attempts to erase Indigenous communities. Although it has been centuries since Mexico was colonized, many aspects of colonization and imperialism have remained throughout Mexico’s societal structures. These structures, in turn, have affected the way that all Mexicans live and are treated based on their identities causing discrimination, humiliation, erasure, violence, and even murder in the belief that certain people are “inferior” or “not human.”

Throughout the years, Indigenous, Queer, low-income, people of color and women have been the victims of this systematic oppression. As a result, these marginalized communities are not allowed to live their true to self-lives peacefully and must fight to survive and for an opportunity to thrive. These groups have created and led many liberation movements and have been to be treated equally and obtain autonomy of their bodies and lives. For instance, in 1979, Mexico City witnessed its first LGBTQ+ Pride Parade, marking an important moment for visibility and activism. In 2003, Mexico City became the first jurisdiction in Latin America to legalize same-sex civil unions. Mexico’s Supreme Court ruled that state bans on same-sex marriage were unconstitutional in 2015, effectively paving the way for nationwide marriage equality. Recently in 2022, Tamaulipas was the last state to legalize same-sex marriage, therefore same-sex marriages became legal throughout the whole county. However, there are still important challenges in place including violence against the Queer community.

Along similar lines, Mexico’s movement against feminicide has emerged as a response to the alarming rates of gender-based violence and femicide in the country. “Femicide” specifically highlights the killing of women due to their gender, often accompanied by elements of machismo and systemic negligence. Since the 1990s, the movement has gained momentum, since the tragic deaths of numerous women and the lack of effective governmental response. The term “femicide” was added into Mexican law in the early 2000s, stated by the United Nations, and the declaration of a gender violence alert in several states, signaling official recognition of the severity of the issue. However, death tolls continue to rise each year, and activists argue that structural issues, such as the culture of machismo, gender-norms and expectations, socio-economic status, race and violence persistently affect the progress. People continue to demonstrate resistance to advocate for justice, safety, and a societal change towards women and AFABs (females assigned at birth) are treated to combat gender-based violence.

Overall, the roots of oppression in México trace back to the colonization from Spain, leaving a lasting impact on the country’s societal structures and systemic biases. The legacy of colonization is evident in the perpetuation of discrimination, humiliation, and violence against Indigenous, Queer, low-income individuals, people of color, and women. Liberation movements, including Queer activism, have played a crucial role in challenging these structures, achieving significant milestones like the legalization of same-sex civil unions and marriage equality. However, there are challenges addressing violence against the Queer community, for they are yet to be seen as equal among society. Similarly, the femicide movement reflects the deep-seated issues of gender-based violence that stems from colonialism. Despite these efforts, the death tolls continue to rise, highlighting the need for sustained resistance against ingrained cultural norms, gender expectations, socio-economic disparities, and systemic violence. The journey toward justice, safety, and societal change remains, but with the ongoing resistance of activists and from the communities, one day they will be able to live authentically and free from oppression.

The Case: The Vulnerability of Trans, Gender-diverse People and Cis-Gender Women in Mexico

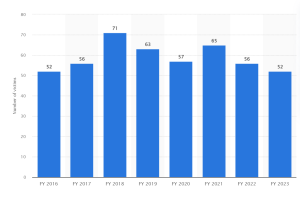

Trans and Gender-diverse People Murdered in Mexico FY 2016-FY 2023

The shocking number of murders of trans and gender-diverse individuals in Mexico from fiscal year 2016 to 2023 demonstrates the persistent violence against this community. In 2016, there were 52 reported victims, a figure that increased to 56 in 2017 before sharply rising to 71 victims in 2018. While there was a slight decline in 2019 with 63 victims, the following years were fluctuating but still with consistently high numbers. In 2020 a total of 57 victims was recorded, and 2021 witnessed a further increase to 65 victims. In 2022, there was a slight decrease to 56 victims, but there was still a threat of violence towards the community. As of the latest update in 2023, the number stands at 52 victims, but these numbers might still increase. Published by the Statista Research Department on November 15, 2023, this data highlights that Mexico is the second country with the highest number of murders of trans and gender nonconforming individuals in Latin America during this period. It is important to note that there is a high chance that this data is not as accurate due to trans and gender-based violence being undermined and overlooked by authorities. Overall, these statistics emphasize the urgent need for comprehensive efforts to address and combat violence and protect the rights and lives of trans and gender-diverse individuals.

(Published by Statista Research Department, Nov 15, 2023)

Between October 2022 and September 2023, at least 52 trans or gender-diverse people were murdered in Mexico. Mexico ranked as the second country with the highest number of murders of trans people in Latin America during that same period of time.

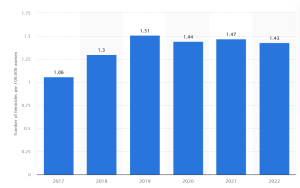

The femicide rate in Mexico from 2017 to 2022, as reported by the Statista Research Department on November 28, 2023, reveals an escalation in gender-based violence against women/assigned female at birth individuals. In 2017, there were 106,000 reported victims, a number that dramatically increased to 130,000 in 2018 and further surged to 151,000 in 2019. Although 2020 saw a slight decrease with 144,000 victims, the numbers remained alarmingly high in following years, with 147,000 victims in 2021 and 143,000 victims in 2022. As of recently, Mexico stands as the second-highest nation for femicides in Latin America, demonstrating a deeply rooted crisis. Based on an article by Vision of Humanity, it can be believed that the reported figures likely underestimate the true scale of the issue, given the substantial number of unreported and uninvestigated instances. The consistent nature of these aggressive crimes is particularly disconcerting, often involving perpetrators with familial or communal affiliations. Despite the government’s introduction of social initiatives such as helplines, the outcomes have not been as successful. Making activists and the community pushing for social activism in order to demand justice and safety for the female population.

(Published by Statista Research Department, Nov 28, 2023)

In 2022, it was estimated that the national femicide rate in Mexico stood at 1.43 cases per 100,000 women.

The Case: Threats to Feminist Collectives in Mexico

Dawn Marie Paley’s article, “How Mexican Feminists Became Enemies of the State,” delves into the challenges faced by feminist collectives in Mexico. The article highlights how feminist movements, considered threats by the state, unite against various issues, from racism to labor rights. Analyzing the strategies employed by these collectives provides valuable insights into the broader activist landscape in Mexico.

A leaked list from the Mexican Secretary of National Defense, revealed by the Guacayama collective, exposes the state’s surveillance on various groups, including feminist collectives, highlighting the government’s attention to the feminist movement. Despite a perceived progressive shift with the election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador in 2018, there are concerns due to non-sufficient measures provided for the safety of women because of the influence of more conservative politicians in power including Lopez Obrador. Feminists have been critical of the government’s militarist and conservative turn, leading to accusations of being opposed to change.

Women in Mexico are actively organizing against various forms of violence, uniting across different spheres of life, their unity challenges the patriarchy in daily life and politics. Feminists engage in diverse struggles, including “anti-racism, memory preservation, searching for the disappeared, defending water and territory, labor rights, justice, the right to free, safe, and legal abortion, supporting migrants, advocating for marijuana legalization, opposing violence, and promoting peace.” (Parley) understand the dynamics of feminist resistance and the attempts to derail the movement, interviews with activists Alicia Hopkins and Lirba Cano shed light on their project: the Comuna Lencha Trans and Cuerpos Parlantes. Their roles are to build autonomy and create feminist spaces in Mexico City and Guadalajara, respectively. The tangible impact of these spaces is evident in the activities they host, contributing to education, organization, and empowerment within the feminist movement. The experiences shared by Hopkins and Cano emphasize the importance of feminist mobilizations and the transformative power of being in the streets, participating in collective actions that show a sense of collective power and the potential for positive change.

The Case of La Comuna Lencha-Trans

The article “Inside La Comuna Lencha-Trans” by Karen Castillo and Fernanda Peralta explores a specific community within Mexico City that serves as a refuge for queer individuals. This community not only provides support but also challenges oppressive systems by existing openly in a conservative environment. Examining this case study helps us understand how grassroots efforts contribute to resistance and community building, highlighting the resilience of marginalized individuals.

La Comuna, is situated in the heart of Mexico City and is a community space run by lesbians, trans people, and cis-gender women. It functions as both a refuge for the queer community and a place for resistance founded in January 2020. Initially it was a community kitchen hosting poetry events but faced challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite reopening in May 2021, economic stability remains a struggle to maintain an autonomous stance, but the community continues to reject funding from political parties or the state. La Comuna serves as a platform to address discrimination, violence within the Queer community, and to support anti-capitalist and anti-systemic movements.

The collective at La Comuna emphasizes the importance of community living and mutual support to thrive in a city plagued by issues like discrimination, gentrification, and violence against queer people. This space has fostered economic and emotional support, enabling members to navigate the hostile external environment. In response to the challenges they face, La Comuna organizes events, workshops, and activities to cover living costs, embracing a holistic approach that includes political education, economic sustainability, and emotional well-being. The collective’s rejection of capitalism and patriarchy underscores the interconnected nature of these systems, shaping their political philosophy.

The internal struggles within La Comuna, such as overcoming toxic patterns and individualism, reflect the ongoing work required to maintain a collective living space. Emotional intelligence has been considered crucial to address internal conflicts, fostering understanding and acceptance among community members. Despite external challenges, including hate crimes, the collective has remained resilient, offering a safe space for Queer individuals facing violence and discrimination. La Comuna’s refusal to engage in divisive debates, such as trans-inclusive versus trans-exclusionary feminism, allows them to concentrate on building community principles and collaborating with movements seeking autonomous resistance.

This space represents a refuge and a place where they can authentically express themselves in a city where their identities threaten conservative values. People can have the ability to gain personal growth and offer an alternative to the cruelty of society. La Comuna’s welcoming environment fosters a sense of love, respect, and protection, encouraging individuals to actively combat patriarchy, racism, colonialism, and hatred towards queer bodies. The collective’s commitment to creating a small world within oppressive systems reflects the transformative potential of community living and resistance.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this exploration of activism and resistance in Mexico reveals the intricate web of challenges faced by marginalized communities, particularly those identifying as queer and women. The historical roots of oppression stemmed in colonization and imperialism, continue to shape societal structures, leading to discrimination, violence, and even murder against Indigenous people, Queer individuals, low-income individuals, people of color, and women.

Insights of theorists like Audre Lorde, Gloria Anzaldúa, and Kimberlé Crenshaw provide critical lenses for understanding the complexities of activism in Mexico throughout their framework. Lorde’s call for embracing differences as a source of creativity and power resonates deeply, urging a shift toward new systems that empower marginalized groups. Anzaldúa’s concept of La Mestiza Consciousness illuminates the struggles of individuals navigating intersecting identities, challenging societal norms, and advocating for the acceptance of diverse forms of existence. Finally, Crenshaw’s intersectionality lens highlights the need to recognize and address the multifaceted nature of violence faced by women and trans and gender-diverse people, emphasizing the importance of considering dimensions like race and class often overlooked in identity politics.

Analyzing feminist and queer activism in Mexico is particularly crucial both movements are perceived as threats to the state, as revealed by Dawn Marie Paley. Despite being on the forefront of various issues, from racism to labor rights, feminist collectives face government surveillance and challenges to their progress. Similarly, the experiences of activists, such as those in La Comuna Lencha-Trans, exemplify grassroots efforts to provide refuge and resistance. La Comuna’s rejection of capitalism and patriarchy, internal struggles, and commitment to community principles showcase the transformative potential of collective living and resistance in the face of societal hostility.

Moreover, the data on the number of trans and gender-diverse individuals murdered and the femicide rate in Mexico reflects the urgent need for comprehensive efforts to combat violence, protect rights, and challenge systemic biases. The statistics, while alarming, underestimate the true scale of the issues due to underreporting and systemic negligence.

In sum, queer and feminist activists in Mexico face ongoing struggles yet also show high levels of resilience. Their experiences highlight the need for comprehensive, and inclusive efforts to dismantle oppressive systems, recognize intersectionality, and create spaces for marginalized communities to thrive authentically and free from oppression. The journey toward justice, safety, and societal change is ongoing, fueled by the determination of those who resist and the hope that one day, these communities will live authentically and liberated. Activists’ efforts and the resistance created by the communities they have created need to be applauded, acknowledged, and followed. Despite multiple forms of oppression, the harsh opposition to their survival, and the violence they face, these communities have survived and found ways to thrive.

References:

Anzaldúa, Gloria. “La Conciencia de la Mestiza.” Feminismos, 1987, pp. 765–775, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-14428-0\_44

Castillo, Karen, and Fernanda Peralta. “Inside La Comuna Lencha-Trans, a Queer Space of Refuge and Resistance in the Heart of Mexico City.” Shado Magazine, 28 Sept. 2022, www.shado-mag.com/act/inside-la-comuna-lencha-trans-a-queer-space-of-refuge-and-resistance-in-the-heart-of-mexico-city/

Crenshaw, Kimberle. “Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color.” Stanford Law Review, vol. 43, no. 6, 1991, p. 1241, https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

Femicide rate in Mexico from 2017 to 2022, Statista Research Department, Nov 28, 2023, https://www.statista.com/statistics/979065/mexico-number-femicides/#:~:text=Mexico%3A%20femicide%20rate%202017%2D2022&text=In%202022%2C%20it%20was%20estimated,1.43%20cases%20per%20100%2C000%20women.

Lang, Sabine. “Native American men-women, lesbians, two-spirits: Contemporary and historical perspectives.” Journal of Lesbian Studies, vol. 20, no. 3–4, 2016, pp. 299–323, https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2016.1148966.

Lorde, Audre. The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House. Penguin Books, 2018.

United Nations. “We’re Here to Tell It:” Mexican Women Break Silence over Femicides, 3 July 2023, www.ohchr.org/en/stories/2023/07/were-here-tell-it-mexican-women-break-silence-over-femicides.

Number of murders of trans and gender-diverse people in Mexico from FY 2016 to FY 2023, Statista Research Department, Nov 15, 2023, https://www.statista.com/statistics/1276994/number-trans-murders-mexico/

Paley, Dawn Marie, et al. “How Mexican Feminists Became Enemies of the State.” NACLA, 11 Apr. 2023, www.nacla.org/mexican-feminists-enemies-state.

Pandit, Puja. “Understanding the Dynamics of Femicide in Mexico: Mexico Peace Index.” Vision of Humanity, 17 Oct. 2023, www.visionofhumanity.org/understanding-the-dynamics-of-femicide-of-mexico/.

Press, The Associated. “Thousands in Mexico Demand Justice for LGBTQ+ Figure Found Dead after Death Threats.” NPR, NPR, 14 Nov. 2023, www.npr.org/2023/11/14/1212836187/thousands-in-mexico-demand-justice-for-lgbtq-figure-found-dead-after-death-threa.

Romero, Simon, and Emiliano Rodríguez Mega. “Killing of Mexico’s First Nonbinary Magistrate Alarms L.G.B.T.Q. Community.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 14 Nov. 2023, www.nytimes.com/2023/11/14/us/mexicos-nonbinary-magistrate-dead.html?smid=url-share.