2 Let’s start at the very beginning

And the beginning for studying any history is a map, to understand where we are focusing our attention. There is an endless supply on the internet. You can even draw your own with tools such as MapHub – I drafted this one here as an exercise in locating areas of major agricultural development in the Chinese region, what geographical features characterize those areas, and so on. Doing this exercise will soon let you identify areas where a prevalent crop is cultivated. Food production depends on climate and geography.

Neolithic cultures

We being our story during the Neolithic era (10,000–1,500 BCE), both to learn our way around the Chinese region and also because the agricultural developments that started at the time will remain regular feature of the Chinese diet, building in their identity.

During the Neolithic, agriculture is concentrated around the two major rivers of China, the Yellow River and the Yangtze. These are the north and south references, and around them the first Neolithic cultures developed. If we were to give a simplified account, we would say that the north is characterized by the cultivation of millets, to which overtime soybeans and hemp seeds were added. In the south, rice prevails. The cultivation of rice is water intensive. While the Yellow river in the north was a source of water to irrigate, rice cultivation also requires milder temperatures than the dry, cold winters that hit the north.

Did you know? The Neolithic is the name of the second phase of early human developments. It succeeds the Mesolithic (when hunt and gathering being to become prevalent, and there are initial developments in the production of pottery) and the Bronze Age (characterized by the discovery and production of bronze). These are subdivisions of the Holocene, the current geological era.

Now that we have clear this basic division, let’s complicate the picture a bit further. Early Neolithic sites concentrate in four areas, two in the south and two in the north. In the south, they are situated along the Yangtze River – the middle section (today’s Northern Hunnan) and the lower section (where today is Hangzhou). In the north, a cluster of sites are located in today’s Hebein, Shanxi, and Shandong. A second cluster is located at the intersection of today’s Liaoning and Inner Mongolia. All these sites take their names after the village or city in which they are located, and this often also gives the name to the culture associated with those sites.

The early Neolithic cultures developed in these four regions share some traits:

- stable cultivation of crops;

- production of instruments, in particular use of pottery tools;

- architectural developments that point at an increasingly sedentary life (houses, storage facilities, and cemeteries);

- evidence of initial domestication of animals.

Increasingly, researchers are discovering more sites and adding their locations to this central area identified initially. The are also identifying more plants that contributed to the diet of early Neolithic inhabitants. A group of sited in the very south of Guandong province, along the coast, contain traces of Canarium nuts, used by the local gather-hunters both in their alimentation and in rituals. The Canarium nuts were widely attested in sited of the South-Asia region (Philippines, Vietnam), suggesting possible connections. The evidence analyzed suggests an even larger set of connections throughout the entire Eurasian continent already around 9000 Before Present (BP)[1], in what has been called a moment of “food globalization in prehistory” that long predates the Columbian Exchanges.

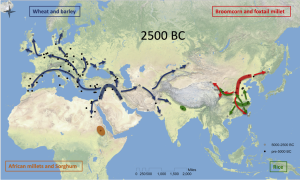

Continuing this line of inquiry, a more recent study[2] has hypothesiszed cereal crops and their movements including Northern Africa, suggesting changes in the diets of all the peoples involved by the second millennium BCE.

Mapped movements of crops by Xinyi Liu et al. 2019, all right reserved.

All of this evidence belongs to prehistorical developments. By convention, the “Neolithic” beings with the use of pottery, and “History” begins with writing. The first written records in China, dated to much later, around circa 1300 BCE, are by and large records of divination, questions asked to gods and deceased ancestors to have indications on how to proceed, or to try predict the future. These are the “oracle bone inscriptions” 甲骨文, so called because they are inscriptions on animal bones used to divine. They dated the Shang 商 dynasty, the first dynasty in Chinese history for which there is ample evidence of it being a complex political structure. Because of their nature, the oracle bone inscriptions do not reveal much about the production and consumption of food. The bones however do: they tell us what animals were captured and/or domesticated for consumption and usage in ritual practices. We discuss this in the next chapter about the Shang and Zhou dynasty.

How do we know what we know?

What is known about food cultivation and consumption comes primarily from archeological evidence. The picture above has been put together thanks to archeological excavations and the development of archaeobotany as a discipline, which studies the organic remains recovered by archeologists. From this, assumptions ad conjectures are made. The more data available, the more these studies can be refined and adjusted.

Archeologically recovered evidence includes more than organic remains. Potteries, weapons, written records, jewelry and musical instruments -to name a few- were recovered in tombs. How evidence reaches us is important to understand the very nature of these elements. The other large body of evidence is known as transmitted evidence, so named because it has been transmitted from generation to generation. Texts and paintings are two major categories. This evience is equally important, but there are two aspects to keep in mind:

- often, writings about ancient times are not contemporaneous to the events being described. They are put together much later. For example, in the philosophical text Hanfeizi 韓非子 there is a reference to Zhou 周 dynasty’s eating habits, yet hundred of years separate the people being described in the text and the compilation of the text.

- in the process of transmitting evidence, our ancestors made mistakes, edits, added and/or removed sections, made what they deemed to be corrections.

Historians, especially those who specialize on ancient times, often find themselves in a dilemma: their primary sources to understand the past are only partially reliable, and it can be challenging to understand which parts are and which ones are not.

It is important to understand the magnitude of archeological discoveries. As a discipline, archeology is a rather recent one: proper methods to excavate and preserve the materials were developed in the last 200 years, with the most revolutionary discoveries happening in the 20th century. Before that, rich men collecting antiquities helped preserving and transmitting through generations ancient objects. Artifacts found in tombs are precious because they are something like time capsules. They have not changed since they have been buried. This does not mean that we can always take these sources as factual or accurate, since we do not know what has happened before they were buried underground. But they do bring scholars a step closer to seeing the state of things in the moment the tomb was closed.

A prehistorical meal

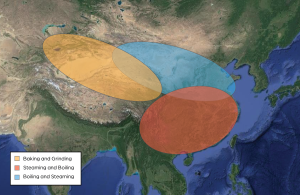

Besides identifying the types of plants being used and domesticated, a recent study has also proposed how these were cooked before consumption.[3] Using bone collagen (a protein) in skeletal remains from around the fifth and fourth millennia BCE, Liu and Reid identified three potential culinary methods by 2000 BCE, as shown in fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Proposed culinary traditions in China, after Liu Xinyi and Reb Reid (2020) The prehistoric roots of Chinese cuisines: Mapping staple food systems of China, 6000 BC–220 AD, page 4.

What determined the development of localized habits in treating food? Liu Xinyi and Rachel Reid, authors of this study, point at two factors: environmental and cultural conditions. Other scholars have identified similar drivers behind the Columbian Exchanges: ecological opportunity, economic relations, and cultural identity.[4] Assuming the Neolithic cultures were motivated by similar reasons, it is possible to explain these local culinary developments as deriving from climate changes, desire to have high-yielding crops, and the gradual formation of cultural preferences.

What determined the development of localized habits in treating food? Liu Xinyi and Rachel Reid, authors of this study, point at two factors: environmental and cultural conditions. Other scholars have identified similar drivers behind the Columbian Exchanges: ecological opportunity, economic relations, and cultural identity.[4] Assuming the Neolithic cultures were motivated by similar reasons, it is possible to explain these local culinary developments as deriving from climate changes, desire to have high-yielding crops, and the gradual formation of cultural preferences.

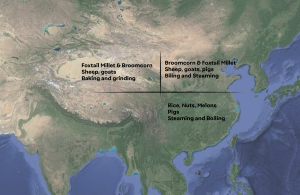

If we were to summarize all the information above of what was being consumed, how, and where, the final picture for developments around 2500 BCE would look something like this:

THE INSTRUMENTS

We have now a general idea about what was being eaten, and how it was being cooked. What is left is examining the evidence for the tools developed to aid the production and consumption of food. As mentioned already, pottery is often taken as the marker for the beginning of the Neolithic. Because of the timespan, there are several Neolithic cultures (you can see a mapping in this Wikipedia page), some more prevalent, and thus well-studied, than others. These cultures interacted with each other. They also developed distinctive features in their production of instruments, due to both cultural aspects and also availability of raw materials. The Yangshao culture 仰韶文化 , which developed around the Yellow River from 5000 to 3000 BCE, is characterized by red-colored pottery such as this pottery basin, or this more elaborate cauldron used above a source of heat. The Longshan culture 龍山文化, which developed later in the same area (3000 – 1900 BCE), is associated with black pottery. These examples indicate that the Longshan culture had developed the turning wheel, and was thus able to produce more refined objects, such as these cups.

Even though scholars attempt to interpret drawings and assign meaning to decorations, it is still unclear whether the embellishments did carry a message. Several of these objects were not every-day tools: some were recovered in times, and at that time, a person had to play an important role to have objects buried with them. The quality of the objects also suggest that these may have been used in ritual practices. In all likelihood these objects were modeled after everyday tools, and are thus a good indication of the instruments that commoners used to produce and consume food.

- Where the "present" in Before Present is not the year in which you live, but the year 1950. ↵

- Liu Xinyi, Reid REB (2020) The prehistoric roots of Chinese cuisines: Mapping staple food systems of China, 6000 BC–220 AD. PLoS ONE 15(11): e0240930 Martin Jones , Harriet Hunt , Emma Lightfoot , Diane Lister , Xinyi Liu & Giedre Motuzaite-Matuzeviciute (2011) Food globalization in prehistory, World Archaeology, 43:4, 665-675. ↵

- Liu X, Reid REB (2020) The prehistoric roots of Chinese cuisines: Mapping staple food systems of China, 6000 BC–220 AD. PLoS ONE 15(11): e0240930 ↵

- Jones, Martin, Harriet Hunt, Emma Lightfoot, Diane Lister, Xinyi Liu, and Giedre Motuzaite-Matuzeviciute. “Food Globalization in Prehistory.” World Archaeology 43, no. 4 (December 2011): 665–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2011.624764. ↵